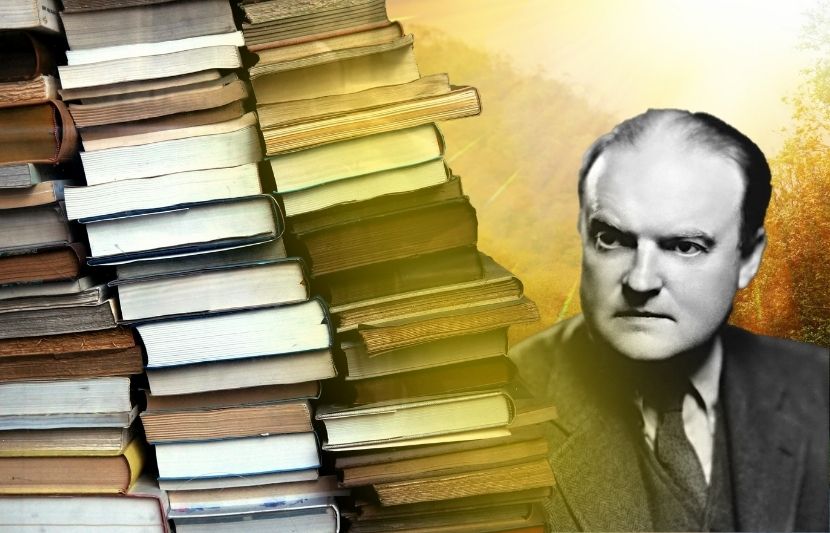

With Memorial Day around the corner, it’s time to raid your bookshelves, peruse your local library, or hit up your nearest and dearest for summer reading recommendations. And if your to-read list is already tottering, you’re in good company: none other than Edmund Wilson, the leading literary critic of his day, who set the idea for Library of America in motion, was a voracious warm-weather bookworm, devouring dozens of tomes while vacationing at his Upstate New York home.

Below, writer Danny Heitman takes a closer look at the books Wilson spent his summers with, from Anthony Powell’s opus A Dance to the Music of Time (“a kind of watered-down British Proust,” according to Wilson) to the enthralling short stories of Ivan Turganev.

by Danny Heitman

Summer can be a season of vexing abundance for readers—a time when there are often more books by the beach chair or backyard hammock than anyone can tackle before Labor Day.

But that didn’t stop Edmund Wilson, one of America’s most avid bookworms, from trying. Wilson, the nation’s dominant literary critic from the 1920s until his death in 1972, pored over poetry, essays, and fiction throughout the year, but his summers in upstate New York often afforded some of the best hours for reading. Settling in for vacation season several decades ago, he picked more than two dozen titles to keep him company.

Reading rested at the heart of Wilson’s essays, which ranged with encyclopedic authority over much of the Western canon, from William Makepeace Thackeray to William Faulkner, Jane Austen to Gertrude Stein, Thornton Wilder to W. B. Yeats. The best of his criticism fills two volumes in the Library of America series. It’s a fitting tribute to Wilson, who was an early advocate of definitive editions of American literature—the concept eventually realized with LOA’s creation.

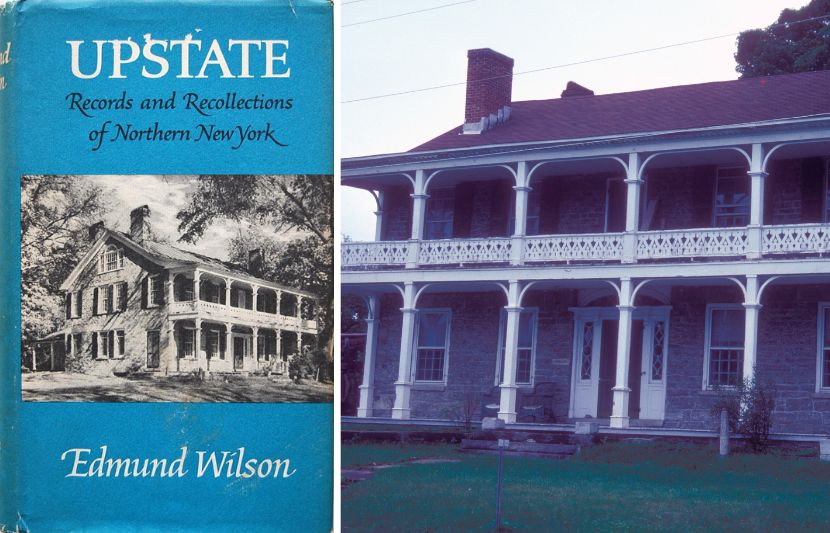

In 1971, as his failing health conspired to nudge him from the national scene, Wilson staged a final literary hurrah with the publication of Upstate—a memoir, written largely in journal form, that recounted his lifelong connection with his ancestral house in Talcottville, a small community near Utica, New York. The old manse was Wilson’s summer refuge, a place where his time with books could unfold with fewer interruptions.

First-edition cover of Upstate by Edmund Wilson (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971) and Wilson’s house in Talcottville, NY (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Upstate sold unexpectedly well, perhaps buoyed by its chatty and casual tone. Nowhere is that sensibility more evident than in an entry from June 7, 1956, in which Wilson appears to clear his throat with three simple words: “Reading this summer.” What follows is a towering stack of titles described over nine pages. It’s an eclectic list heavily weighted toward the cerebral, though Wilson gossips about books with such verve that even the most ambitious ones seem to meet us at street level.

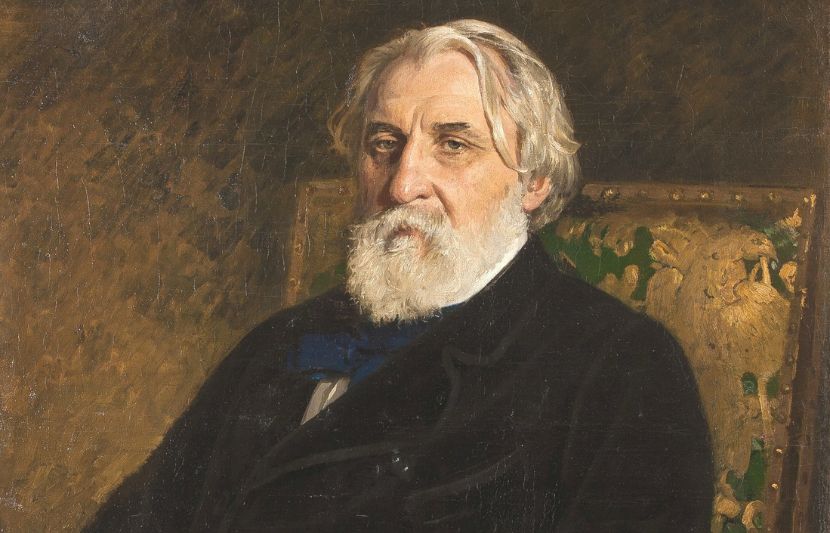

He starts by listing Ivan Turgenev’s “The Inn” without comment, perhaps assuming his readers already know about this nineteenth-century story by the Russian master. A mention of Alone, a memoir by the novelist and travel writer Norman Douglas, merits more comment, mostly negative. “Too much of this book,” Wilson laments with customary puckishness, “is complaint about not being able to get good wine or the right kind of macaroni.”

After picking up one book after another, Wilson seems to find in Turgenev at least one writer who enthralls him, hinting at the kind of rapture every summer reader seeks.

Donald Elder’s biography of Ring Lardner makes Wilson equally glum. “It is depressing to read about Lardner—so unsatisfied as a writer and actually so inadequately equipped,” he sighs.

Charles Angoff’s biography of social critic H. L. Mencken does little to lift Wilson’s mood: “I felt, after reading the book and Don Elder’s book about Lardner, that the twenties had been a squalid period.”

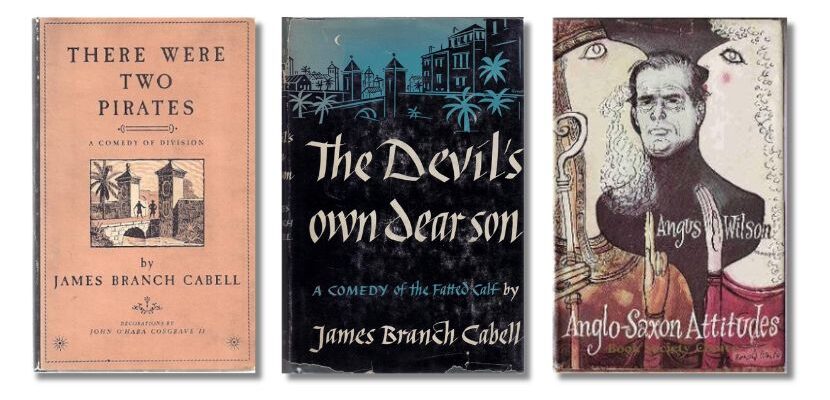

Two fantasy novels by James Branch Cabell, There Were Two Pirates and The Devil’s Own Dear Son, get a qualified thumbs-up: “Not bad, but not of his best.”

A sampling of Wilson’s summer reading: There Were Two Pirates and The Devil’s Own Dear Son by James Branch Cabell and Anglo-Saxon Attitudes by Angus Wilson

Wilson gives a similarly backhanded compliment to Time and Place, a memoir by the British broadcaster and political operative George Scott: “Read a good deal of this without expecting to when I picked it up . . .”

Anglo-Saxon Attitudes, Angus Wilson’s fictional satire of British society, was on the American Wilson’s summer reading list that year, too. It almost passes his inspection: “His best book up to date; but I don’t quite believe in his middle-aged heroes who get themselves muddled up and then make a moral effort to straighten themselves out.”

In the summer of 1956, Wilson was also dipping into Anthony Powell’s multivolume fictional saga A Dance to the Music of Time, which was still a work in progress. Wilson offered no encouragement to Powell to carry on, describing the project as “a kind of watered-down British Proust. The Proustian observations on human life are largely unsuccessful: the Latin of Proust’s style in French sounds rather pompous in English, and Powell is not profound or poetic.”

Mencken’s Minority Report, a collection of his aphorisms, was another volume in Wilson’s already teetering summer TBR pile. “I have been trying to read this posthumous book of notes,” he groused, “but I doubt whether I’ll ever get through it. Some of the paragraphs are effective: characteristically clear and crackling; but his ideas, stated baldly, are very often quite stupid.”

Wilson ends his summer reading list with an echo of where he started, mentioning “Two Friends,” another story by Turgenev. “I have been reading Turgenev straight through and, though I break off from time to time, have never lost my appetite for him,” he confesses. After picking up one book after another, Wilson seems to find in Turgenev at least one writer who enthralls him, hinting at the kind of rapture every summer reader seeks.

1874 portrait of Ivan Turganev by Ilya Repin (Public Domain)

If Wilson’s survey of his summer reading appears a bit world-weary, it’s perhaps because his standards for books were so high. He wanted them to be better than life itself, as he argued in “The Pleasure of Literature,” a 1938 essay in the first LOA anthology of Wilson’s criticism: “O indispensable books! O comforting alternative worlds, where all discords are finally resolved, if not by philosophy, then by art—how without you should we reconcile ourselves to this troublesome actual world?”

The year after Upstate’s publication, Wilson died in Talcottvile on June 12, 1972. He was in his summer house, and it was full of books—at least some of them, we assume, still unread.

Danny Heitman, editor of Phi Kappa Phi’s Forum magazine, frequently writes about books for The Wall Street Journal, The Christian Science Monitor, and other publications. He is also a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate and the author of A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.