Mystery & Crime

Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961)

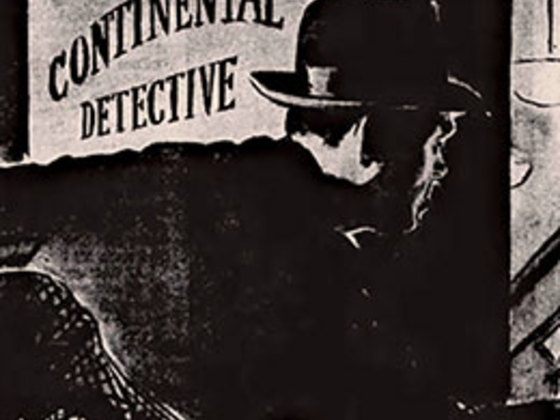

From Dashiell Hammett: Crime Stories & Other Writings

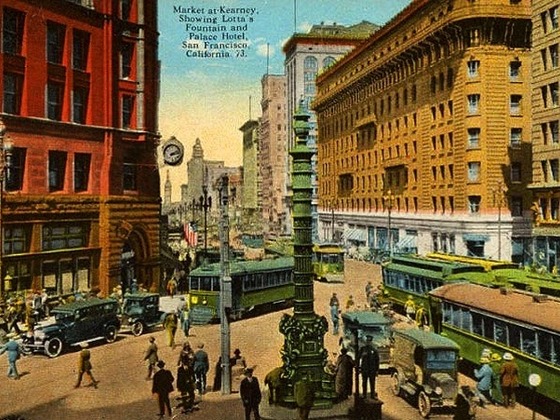

When Dashiell Hammett’s novels began appearing at the end of the 1920s, reviewers frequently compared him to Ernest Hemingway, whose best-selling novel The Sun Also Rises had been published in 1926. Extolling Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest (1929), the critic in Bookman magazine wrote, “It is doubtful if even Ernest Hemingway has ever written more effective dialogue than may be found within the pages of this extraordinary tale.” Across the pond a year later, a reviewer praised The Maltese Falcon, noting that “the writing is better than Hemingway, since it conceals not softness, but hardness.” That was all Hammett’s publisher needed to take out ads with the boldfaced headline “Better than Hemingway.”

What the two authors thought of each other is not entirely clear—and it certainly changed over time. In 1926, just before Hammett began working on Red Harvest, he included in the short story “The Main Death” a scene in which a central character is reading The Sun Also Rises. Five years later, he told an interviewer that the three living writers he admired most were Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ben Hecht. For his part, Hemingway asked his editor, Maxwell Perkins, to send him in Madrid a copy of The Glass Key as soon as it came out. And in the travel account Death in the Afternoon (1932), Hemingway recalled that when his eyes were “bad,” his wife read The Dain Curse (“his bloodiest to date”) aloud to him, mumbling past the more violent descriptions so the children wouldn’t hear.

The mutual respect was tested, however, when the two authors finally met and hung out in the same circles—and who was more offensive often depended on who was more drunk. One night, Hemingway inexplicably threw a highball glass at the fireplace and an equally intoxicated Hammett lashed out at Hemingway’s machismo and disparaged his literary depictions of women (“He only puts them in his books to admire him”). On another occasion, at the Stork Club in New York, Hemingway provoked various people in the crowd and began taunting Hammett, who told him to stick to bullying Fitzgerald and promptly left the club.

An ongoing debate among scholars and fans concerns who influenced whom. While Hemingway was first to publish his writing in book form, Hammett’s stories began appearing in magazines years earlier—mostly in Black Mask, which was probably not readily available to Hemingway, living in Paris at the time. Hammett biographer William F. Nolan probably has it about right, however: “They might be compared to a pair of scientists, an ocean apart, working on the same experiment, each solving it independently.”

For our Story of the Week selection, we return to the earlier, less contentious years and present “The Main Death,” a puzzle mystery in which the young woman reading Hemingway has to deal with a husband who is more interested in her activities than in how $20,000 has gone missing when an employee is shot and killed.