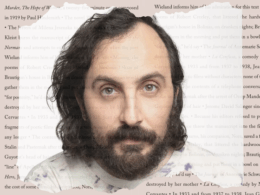

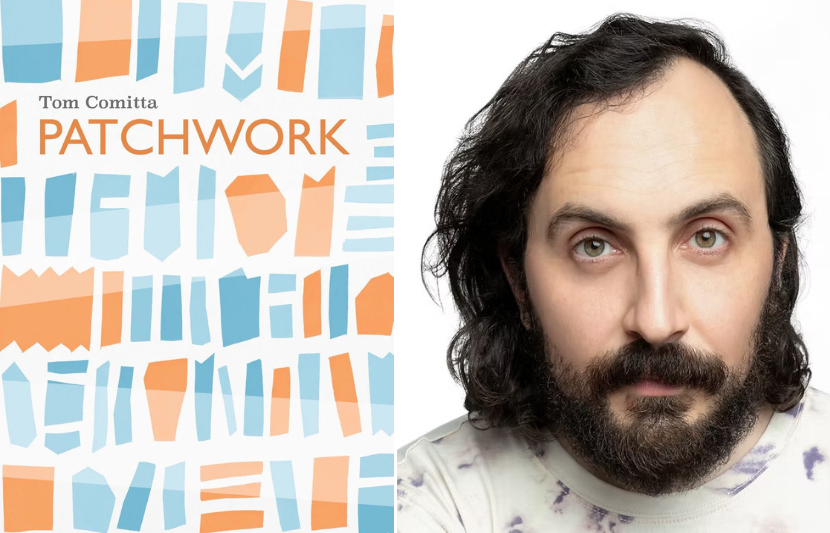

Patchwork by Tom Comitta (Coffee House, 2025); photo: Beowulf Sheehan

Practitioners of the cut-up have long stitched superficially disparate literatures together, flattening differences and drawing out unexpected points of connection. Now, to the newspaper insertions of John Dos Passos’s U.S.A trilogy, the Beat experiments of William S. Burroughs, and the gnomic fragments of David Markson, we can add Tom Comitta’s Patchwork (Coffee House, 2025), a raucous, provocative, and surprisingly moving novella-in-pieces, assembled from the shards of more than sixty classic works (a brief spin through the book’s entrancing “Sources” section turns up everyone from Edgar Rice Burroughs to Octavia E. Butler, Don DeLillo to Barbara Kingsolver).

“When the lights go dark, I take comfort in knowing we will always have Tom Comitta’s art,” writes author Paul Yoon. “Their new book, Patchwork, is quite simply wondrous: it’s like the love child of a Yorgos Lanthimos film and Anne Carson’s poems, with a wild corner of a Hieronymus Bosch painting peering over your shoulder. Every page is filled with enormous heartbreak and danger but also with enormous love and technicolor—a book that flies into your dreams and plucks magic from deep down.”

Below, Comitta describes two genre-defying texts that shaped their thinking about the ephemerality of prose and the unaccountability of the writing life, as well as an archive of their own selected “missing pieces.”

Elsewhere, I’ve mentioned that the next time I teach a writer’s workshop, the first thing we’ll read is Renee Gladman’s TOAF: To After That. The second book we’ll read is Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces. TOAF is the best example I’ve seen of an author improvising in the face of a creative block: Gladman has written an entire book—part memoir, part essay—about her own self-proclaimed failed novel, After That. An homage that gives this abandoned text new life, TOAF also offers an honest portrait of what actually goes into creating a work of fiction.

To After That (TOAF) by Renee Gladman (New York Review Books, 2024)

The Missing Pieces points to another central aspect of the writing life, but one that few talk about: not writing. Like Patchwork, this book is a supercut—or an accumulation of textual similarities—but here it’s all nonfiction. Lefebvre, a poet who runs the publishing house Les Cahiers de la Seine, has collected thousands of gaps in the lives and works of hundreds of writers, artists, and musicians. Over the course of eighty-three pages, we encounter an archive—aka a list—of many writings, compositions, and objects we will never have access to, such as the love letters between Rimbaud and Verlaine; two notebooks by Sylvia Plath; Herman Melville’s marginalia on several books erased by his daughters; the earliest version of Tristan and Isolde; all indigenous artworks destroyed by missionaries; and entire concert halls and libraries lost to fires. The list goes on and on, and even includes things like Pierre Gyotat’s lost hair and Hans Christian Andersen’s singing ability, which supposedly led him to writing. In The Missing Pieces, we never see the things described. We just know they don’t exist. Or not anymore.

The Missing Pieces by Henri Lefebvre (Semiotext(e) / Native Agents, 2014)

But the title is deceiving. Many of the things listed are not simply missing. I was startled to discover how many writers have burnt their own manuscripts over the centuries. And at one point Lefebvre declares the future end of Net Art: “any work of virtual art is hereby condemned to disappear.” While reading The Missing Pieces for a third time, I took a full account of Lefebvre’s categories of erasure, which include flooding, dismantling, bulldozing, theft, being abandoned by their creators, never being started, being written but never published or performed, being eaten by a dog (apparently it does happen!), non-attribution, rejection, self-destruction, confiscation, suppression, and being rolled up and smoked (as the Red Guard did with sixteen drawings Modigliani gave to his lover Anna Akhmatova).

It might seem strange to be inspired by such loss. But in moments of writerly despair—everything from the rejection we all face to questions of writing’s place in a time of institutional and cultural collapse—I find comfort in the fact that all of this is not new. That writers and artists throughout time have confronted personal and societal loss. That so many have arrived at a similar place to Samuel Beckett: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

No one teaches you how to write without student loans or free rides. No one tells you how to adapt to those times when you might only have thirty minutes to write on your way to work.

Even at the most basic writerly level, this seems important. MFA programs teach us to write like machines, cranking out text after text in conditions that are impossible to maintain for the vast majority of graduates. No one teaches you how to write without student loans or free rides. No one tells you how to adapt to those times when you might only have thirty minutes to write on your way to work. That getting started later in life is okay—and that many writers have done this (see The Missing Pieces for a few). That breaks are sometimes—and often—necessary. That an idea marinating in your mind, body, soul over weeks, months, and years can benefit from the delay. That not writing is part of writing.

The list presented in The Missing Pieces is time- and place-stamped. It was compiled in Paris over several years until it was published in 2004 and then translated by David L. Sweet in 2014. As the excess of this textual archive suggests, this book could be much longer. And it would surely benefit from additions by others from other literary cultures. In closing, I thought to share a few additional “missing pieces” I’ve thought of over the years:

The first draft of John Keene’s Counternarratives lost to an MS Word glitch ● The books Kathy Acker could have written had she lived longer ● The widespread recognition of Hilma af Klint’s genius before 2018 ● The precise location in Wales where Arthur Machen had the terrifying vision that inspired The Great God Pan ● The original sheen of Arakawa and Madeline Gins’s Site of Reversible Destiny, still worth the visit ● Komar and Melamid’s “Bulldozer Exhibition,” 1974 ● The San Francisco Art Institute ● The millions of dollars of nonprofit arts funding rescinded by Trump’s NEA ● The six months Tom Comitta didn’t write while getting sober ● The twenty-six years between Joan Lindsay’s first and second book ● The current whereabouts of Sun Ra ● The Winds of Winter, the sixth book in the Game of Thrones series, eclipsed by the TV adaptation and unfinished ● An accurate description of the xenomorph in Alan Dean Foster’s tie-in Alien novel ● Bob Dylan at his Nobel Prize ceremony ● The true identity of Chuck Tingle ● Time spent thinking about Dimes Square that we will never get back ● About $14.99: the amount each author lost when Meta’s AI studied their e-book; 500 metric tons: the amount of carbon burned to create GPT-3 ● The thousands of manuscripts left in the slush pile each year ● James Patterson’s love for James (“Sleep Aid”) Joyce ● Fran Ross’s second novel ● Dambuzo Marechera’s activities in his final months on Earth ● Gary Indiana’s library; the homes, paintings, and writings of Marwa Abdul-Rahman, Robbie Dewhurst, Christina Quarles, and Ross Simonini; and all the other homes and art lost to the Eaton Canyon Fire ● The unpublished, unpresented, and future poems, novels, music, and art created by Refaat Alareer, Hiba Abu Nada, Mohammad Abdulrahim Saleh, Heba Zagout, and thousands of others lost in the Gaza genocide

Tom Comitta is the author of Patchwork and The Nature Book (Coffee House Press) and People’s Choice Literature: The Most Wanted and Unwanted Novels (Columbia University Press). Their fiction and essays have appeared in WIRED, Literary Hub, Electric Literature, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Believer, and BOMB. Comitta works as a book designer and lives in Los Angeles with their partner, child, and pooch.