Over a career spanning nearly seventy years, Gary Snyder has long been recognized as one of America’s pre-eminent poets, a recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, an American Book Award, the Bollingen Prize, and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for lifetime achievement. He is also an unofficial “poet laureate of Deep Ecology,” an influential seeker of alternatives to “the Judeo-Capitalist-Christian-Marxist West,” and for some, a kind of personal sage.

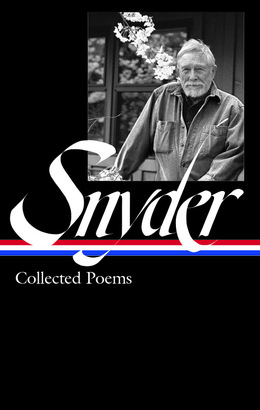

Published in May to coincide with Snyder’s ninety-second birthday, Library of America’s new Gary Snyder: Collected Poems collects all eleven of his books of poetry in one volume for the first time—and also includes a number of uncollected poems, drafts, fragments, and translations in newly authoritative texts that reflect Snyder’s own corrections and revisions.

The book is edited by Anthony Hunt, one of America’s leading Snyder scholars, and Jack Shoemaker, Snyder’s longtime publisher. Hunt is the author of Genesis, Structure, and Meaning in Gary Snyder’s Mountains and Rivers Without End (2004). Now retired as professor of English at the University of Puerto Rico–Mayagüez, and a former Fulbright scholar and Peace Corps worker, he lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Shoemaker is Founding Editor of Counterpoint Press, where he has published (in addition to the works of Gary Snyder) Wendell Berry, Evan S. Connell, M.F.K. Fisher, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and James Salter, among many other writers. He has worked with Snyder for over fifty years.

Via email, Hunt answered our questions about the new Collected Poems.

Library of America: Snyder’s debut collection, Riprap, appeared in 1959, and the translations of the classical Chinese poet Han Shan that he published as Cold Mountain Poems date from a year before that. Those two collections have been paired together for so long that they seem virtually joined at the hip. Does much of Snyder’s early poetry form a kind of dialogue with his Han Shan translations?

Anthony Hunt: Having done some translation work myself, I don’t believe the Han Shan translations should be thought of as “joined at the hip” with Snyder’s other early poems. Normally, the business of translation is a narrowly defined, self-limiting, process. Although it can never be exact, it is a back-and-forth activity that moves between the original and the translated work and sharply focuses on finding the closest fit: the right words, rhythms, and/or images that will convey the intent of the original to the destined work. At times rhythm predominates; at other times images or meanings prevail in the “finished” work.

Still, Snyder says in his “Afterword” to the latest edition of Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems that “there is no doubt that my readings of Chinese poems, with their monosyllabic step by step placement, their crispness—and the clatter of mule hooves—all fed this style” [i.e., the rhythms and insights of a trail crew laborer working with the bedrock of Yosemite National Park as captured in Riprap].

Yet it would be far too limiting to think of all of Snyder’s early poetry as emanating from such rhythms. Written earlier, in 1955, the words and phrases of the poems in Myths & Texts dance to a different rhythm as do many of the poems in The Back Country or Regarding Wave.

More to the point would be his further comment about “the idea of a poetry of minimal surface texture, with its complexities hidden at the bottom of a pool . . .”; these, he says, are poems linked to “the heart of the Chinese shi (lyric) aesthetic.” Although this “lyrical” type of poem is hardly suitable for long poems like those found in Mountains and Rivers Without End, one can find examples of it persisting throughout Snyder’s entire poetic career.

LOA: Reviewing Gary Snyder’s Pulitzer Prize–winning collection Turtle Island in 1975, the late Richard Howard wrote: “There are no symbols in Snyder’s poetry, no metaphors even, nothing ever stands for anything else.” Is that an accurate assessment, and if it is, what kind of poet does that make Snyder, at the level of his language?

Hunt: Clearly, Richard Howard’s statement in his 1975 review of Turtle Island is both provocative and somewhat misleading. Consider that Snyder writes, in separate poems chosen randomly from the book, that “The Dharma is like an avocado!”, or that “Magpie’s Song” about “Turquoise blue” symbolically represents not just an actual animistic conversation with a mythical bird but a sacred invitation to yet another level of consciousness, or that the image of “Dusty Braces” encapsulates the personae of the hard-working, male ancestors who are “stiff-necked / punchers, miners, dirt farmers, railroad men.” There are, of course, more examples.

Myths themselves are metaphorical and, as Snyder explains in his “Introductory Note,” the very title of his book—Turtle Island—is a name for the North American continent “based on many creation myths of people who have been living here for millennia.” Generally speaking, these myths involve a supreme being who sends an animal (such as a turtle) into primal waters to bring back bits of mud or dirt upon which a habitable continent, or earth, or cosmos, may be built. It is a tale told variously by several indigenous cultures in North America; versions may be found in Hindu and Chinese mythology as well. True enough, the direct literary use of “like” or “as” is rarely found in the poetic lines of these poems, yet the very book itself, and each and every one of its poems, may be said to “stand for something else.”

The appeal of Snyder’s poems, especially in this Pulitzer Prize–winning volume, is the way these poems become vehicles, as Snyder writes, that “speak of place, and the energy-pathways that sustain life. Each living being is a swirl in the flow, a formal turbulence, a ‘song.’” The attentive reader of such song-poems inhabits the places and feels that energy both in specific lines and stanzas, as well as in the totality of each poem. His poems move us, drive us back to our fundamental roots, both literally and figuratively. To read a poem like “The Way West, Underground” is to inhabit the circumpolar pathways of “The Bear,” metaphorically and linguistically, from Oregon westward across the North Sea Road to Japan and then onward across the northern steppes to Finland . . . with stops along the way in Tibet and the caves of France and Spain. In the reading of the words of the poem we join this ancient energy-flow.

LOA: At one time it was more common to refer to Snyder as a Beat poet, or at least a Beat-adjacent poet, which is understandable: He read alongside Allen Ginsberg at the Six Gallery in San Francisco in 1955 and inspired a character in Kerouac’s novel The Dharma Bums. But does it hinder our understanding of Snyder’s work to group him with the Beats? How does his work align with theirs, or not?

Hunt: In poetry, prose, and playwriting the Beat Generation authors dedicated themselves to a non-traditional exploration of form and content. Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” is a prime example, as is Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road.

Although he was one of the original poets at the Six Gallery Reading and thus associated with that significant moment in Beat culture, Snyder’s life and work easily transcend the limiting confines of being grouped merely as a “Beat poet.” If “Howl” became the self-centered symbol of Beat poetry, Snyder’s “The Berry Feast,” read on that same October evening in 1955, pointed in a different direction, focusing, as it did, on a communal world of coyotes, bears, and humans.

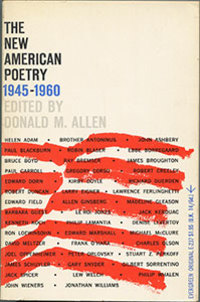

Published a few years later, Donald M. Allen’s influential anthology, The New American Poetry (Grove Press, 1960), divides the poets it includes into five groups, including a category for “Beat Generation Poets.” While Snyder’s name briefly pops up in the discussion of this category—“The Beat Generation . . . first attracted national attention in San Francisco in 1956 when Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso joined Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and others in public readings”—Allen actually places Snyder’s poems under the fifth group of “younger poets who have been associated with and in some cases influenced by the leading writers of the preceding groups, but who have evolved their own original styles and new conceptions of poetry” [emphasis mine].

Remember that he put much of the early Beat influence behind him when he left for Japan in 1956. By the time he establishes his home in the Sierra Foothills, if not sooner, the poems published in Regarding Wave, Turtle Island, and Axe Handles (not to mention Mountains and Rivers Without End and later works) are in a category all their own.

LOA: An environmental or ecological consciousness becomes increasingly central to Snyder’s writing from around the time he resettled in Northern California, in the late 1960s (after more than a decade living abroad). Can you discuss this ecological awareness, and how it is manifested in the poetry?

Hunt: Rather than considering the late 1960s as a turning point of sorts, we can argue that an “environmental consciousness” was always central to Snyder’s thought and writing. How could he not have an “environmental consciousness” from his earliest years? He was raised on a dairy farm in the Pacific Northwest where he says an old growth tree was one of his closest companions. He grew up amid the overwhelmingly beautiful, unforgettable Cascade Mountains. As a member of the Mazamas Mountaineering Community he climbed many of those major peaks before he was twenty years old.

Yet there is so much more, such as his trip to the Seattle Art Museum as a very young boy when he first saw the Chinese scrolls. His awareness of Native American culture is seen in his Reed College thesis on the myths of the Haida nation. Then, in addition to his love of hiking in the surrounding wilderness, there are his stints as a fire lookout on Crater and Sourdough Mountains and his summer jobs working on U.S. Forest Service trail crews and as a choke setter for a logging company. In Japan, in the late 1960s, his friendship with Nanao Sakaki leads to his active engagement with the Banyan Ashram, an ecologically-aware communal living and farming experiment on Suwa-no-se Island. The list of connections that demonstrate his environmental consciousness is, in fact, endless; it is ongoing and central to his very being from his earliest years.

The same consciousness is in his earliest poetry. Although published after Riprap (1959), many of the poems in Myths & Texts (1960) were written while he was engaged as a choke setter on the Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon. The lines of many of these poems refer to the destructive logging practices of the “civilized” world, even from ancient times. His expanding awareness of ecological matters was surely enhanced by the obvious ironies of being personally involved in “cutting down the groves.”

There is also his growing awareness of Buddhist philosophy and thought. To take an example in Mountains and Rivers Without End, the “jeweled net” associated with the Avatamsaka Sutra is an image of radical interconnectedness and interdependence, an image perfectly suited to depict the need for a harmonious relationship among all beings, one that would deny humans the right to serve as overlords to non-human beings. This epic-like poem, the culmination of forty years (1956–1996) of thought and writing, contains multiple instances of interdependence. In “Boat of a Million Years” Snyder writes that “Teilhard said ‘seize the tiller of the planet’ he was / joking, // We are led by dolphins toward morning.” In “Afloat” two people in a skin boat become “two souls in one body, / two sets of wings, our paddles swing / where land meets water meets the sky . . . .” The skin images melt away allowing the reader to merge not just the “two souls,” but the sky world with the water world below, and the human world with all the beings of the natural world. The climatic section of the long poem, “The Mountain Spirit,” includes an intermingled dance of the poet with a twisting, spiraling, Bristlecone Pine, itself an image of universal consciousness.

Examples of “environmental or ecological consciousness” are everywhere in Snyder’s poetry, from Riprap (1959) and Myths & Texts (1960) to This Present Moment (2015). We can also point out the impact of his relevant prose works—such as Earth House Hold (1969), The Practice of the Wild (1990), A Place in Space (1995), or Back on the Fire (1996)—where he writes essay after essay related to his concerrns about the environment. As more than one person has written, Gary Snyder has always been, and is, first and foremost, the “Thoreau” for the ecological movement of our age.

LOA: Snyder’s epic sequence Mountains and Rivers Without End (1996) opens with a reproduction of a Sung Dynasty handscroll. How has Snyder’s engagement with East Asian art and calligraphy been important to his verse?

Hunt: Like “environmental awareness,” it seems that East Asian artistic and cultural influences on Snyder were both profound and pervasive from his earliest years. It’s difficult to pinpoint the origins of this engagement. Snyder has often told the story of his first encounter with Chinese landscape paintings when he was a young boy:

The Cascades of Washington, and the Olympics, are wet, rugged, densely forested mountains that are hidden in cloud and mist much of the year. When I was a boy of nine or ten I was taken to the Seattle Art Museum, and was struck more by Chinese landscape paintings than anything I’d seen before, or maybe since. I saw first that they looked like real mountains, and mountains of an order close to my heart; second that they were different mountains of another place and true to those mountains as well; and third that they were mountains of the spirit and that these paintings pierced into another reality which both was and was not the same reality as “the mountains.”

Never forgotten from his youth, the concept and image, not to mention the very details, of the East Asian landscape scroll have clearly stayed with him.

While an undergraduate at Reed College (1949–1951), he was introduced to calligraphy by his professor (and friend), Lloyd Reynolds, who taught classes in the art of calligraphy at Reed, and a fellow student (and friend) Charles Leong, a Chinese American who was an accomplished calligrapher. To this day, anyone fortunate enough to have a book or letter signed by Snyder knows what a fine, calligraphic hand he has.

Because reproductions of the Sung Dynasty handscroll Endless Streams and Mountains (known in Chinese as Ch’i-shan wu-chin) are included with printings of Mountains and Rivers Without End (1996), readers may be aware of its influence on the work. However, the structure and placement of many of the sections within the complete poem are indebted to the influence of the Japanese Noh play. Snyder’s immersion in that art began in Kyoto shortly after he first moved there in 1956 and it continued after he returned to live and study there in subsequent years. His close friend in Kyoto, Will Petersen, printer-potter-poet, not only was knowledgeable about the Noh in general but was a respected translator (into English) of several Noh plays. (It was Petersen who provided the cover and the drawings for Myths & Texts when it was published in 1960.) In June of 1956, barely a month after his arrival, Snyder wrote to Will Petersen that he had tickets to attend his first Noh performance. Nine months later he wrote to Philip Whalen:

I am fascinated by the kabuki and noh recitation technique—at kabuki one man half-sings half-chants the narrative (in a sort of poem form, alternating 7-5-7 syllable lines) with one or two samisen twangers, occasional wooden clackers & drum. At noh, a flute, a big drum & a little drum, sometimes clackers, are used. Very sparingly. Sometimes the man on the small hand-drum sort of yowls as he hits it. . . .

. . . I can imagine a very jolly creative sort of modern poetry-modern-dance-music shot built around the reading of one long dramatic-type poem with musicians and possibly a dancer. (March 8, 1957. Philip Whalen Papers-Reed College)

East Asian artistic and cultural influences on Gary Snyder have been profound and pervasive throughout his career. There is no way one can mention all the historical-mythological-spiritual figures who have traveled from the landscapes of East Asia-India-Tibet into Snyder’s poetic world—figures as diverse as Tārā, Hsüan Tsang, Ame-no-uzume. Certain poems actually contain calligraphic figures or drawings that have indeterminate meanings. Some poems have subtle rhythms derived from Chinese poetry. Thinking of “The Circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais,” it seems clear that Snyder’s poetry (and practice) is responsible for transferring certain ritualistic meditative practices from the “east” to new landscapes in the “west.” His ongoing artistic interaction with Tom Killion is a further example of an East Asian influence in which Snyder’s work has had a role to play. In the three volumes on which they have collaborated, Killion’s Japanese ukiyo-e style prints of California’s landscapes literally illuminate Snyder’s poetry and prose, and vice versa.

A Chinese landscape scroll commonly has a colophon panel containing written notes or poems pertaining to the scroll that are added by various owners over the centuries. Similarly, in order to “own” Snyder’s poems it is truly up to individual readers to comment in their own fashion on the influences—direct and indirect—that they encounter, influences that are seemingly endless. For now, as the last lines of his long poem Mountains and Rivers Without End state:

The space goes on.

But the wet black brush

tip drawn to a point,

lifts away.

LOA: Gary Snyder: Collected Poems is a rarity in the Library of America series in that it encompasses the life’s work of a living poet. You also had the benefit of working with Snyder himself in the preparation of this book. What were his contributions? Did he have specific recommendations for you?

Hunt: Bringing Gary Snyder: Collected Poems to fruition, especially during the ongoing assault of the Covid-19 coronavirus (in all its variations) when face-to-face meetings were impossible, has been a lengthy, detailed, and fulfilling process. Months of preparation went by involving the selection of poems and the organization of the volume. This was followed by tracking down some early, or even “missing,” poems, noting some duplication, discovering uncollected works, and establishing a working timeline. All these stages actually preceded the work of annotation: moving in an accurate and meticulous manner poem-by-poem and book-to-book.

At each stage, whether it was the verification of newly surfaced poems to occasional matters of poetic clarification (especially when that involved phrases or graphics related to East Asia), Mr. Snyder provided his advice and counsel when asked.

How fortunate we were to be able to share our work with Gary Snyder.