Painting of Stalin by Isaak Brodsky (Public Domain), Hitler giving a speech in 1935 (CC BY-SA 3.0 de), and photo of Hannah Arendt by Ryohei Noda (CC BY 2.0)

Among the twentieth century’s most astonishing and provocative philosophical minds, Hannah Arendt translated her experiences of persecution and exile into an engrossing, necessary analysis of the rise of totalitarian regimes. Positing that dictators like Hitler and Stalin had created, in their party organization and bids for political power, a “lying world of consistency” tailored to the absolute authority of the leader, Arendt sought to both demystify the ascendence of such strongmen and diagnose how so many submitted, seemingly without question, to their inhumane wills.

In the recently published The Origins of Totalitarianism, Expanded Edition, Arendt’s masterpiece receives the Library of America treatment, with reincorporated chapters dropped from earlier editions, a newly researched chronology of her life and career, and extensive textual notes unpacking the context and content of her thinking. Below, Thomas Wild, who co-edited the volume with Arendt’s literary executor Jerome Kohn before his death in 2024, delves into this towering work of politics, history, and human nature, explaining how its author managed to cast light on this dark, diffuse phenomenon with language at once poetic, propulsive, and profound.

LOA: You worked closely on this volume with Jerome Kohn, Arendt’s graduate student and later her literary executor. Could you discuss your collaboration with Kohn before his death last year?

Thomas Wild: When Library of America invited Jerome Kohn and me to welcome Hannah Arendt into the series, we were immediately excited to think together of ways in which Arendt’s writings could be presented, both as a collection of her pivotal books and essays and as an opportunity for readers to experience her work anew. A wonderful feature in this new edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism is a meticulous chronology of Arendt’s life, work, and legacy. Kohn and I greatly enjoyed putting this together, and it will appear in all future LOA Arendt volumes.

Kohn’s dedication to facilitating new ways of engaging with Arendt’s thought drove his work as literary executor and editor alike. Over the past thirty years, he published five collections of texts by Arendt, all of them combining previously unpublished writings from her papers and carefully curated essays and articles that appeared in now obscure journals or newspapers. That’s what keeps an author alive, when new or rare texts and collections become available.

Since Arendt’s death in 1975, Kohn contributed numerous introductions, essays, lectures, and interviews to the world of critical Arendt studies. His insights are always deep and nuanced, his way of speaking thought-provoking and free of jargon. All this shaped our understanding of Arendt’s work globally over the past several decades.

People under totalitarian rule are pressured to approve lies that make the ideological picture of the world consistent, not contested. If it is believed that only the greatness of the Aryan race or the brilliance of the Bolshevik system is capable of creating something as spectacular as, say, a subway, everyone who knows of the existence of the Paris subway is a potential threat.

What is so special, in addition, is that Kohn never wanted to dominate the discourse on Arendt. Being the one domineering voice of interpretation or attention would have been contrary to Arendt’s fundamental notion of plurality. Kohn was truly committed to encouraging other people’s readings and thinking about Arendt.

LOA: This volume of Origins includes two chapters dropped from earlier editions: Arendt’s original “Concluding Remarks” and an examination of the suppressed Hungarian revolution of 1956. What is the value to the reader of having these previously excised materials in the new edition?

TW: Indeed, our edition of Origins presents Arendt’s last authorized version of the text from 1967, together with her original conclusion from 1951. Her fascinating reflections on the Hungarian revolution are not easily accessible otherwise. Readers can trace how Arendt’s thinking about the shifting manifestations of totalitarian rule developed: first, a few years after the end of World War II, when Hitler was defeated but Stalin was still in power; then, after Stalin’s death in 1953, at the moment of a pivotal uprising in Hungary against Soviet domination; and lastly, in the wake of student protests and on the eve of the Prague Spring in 1968.

Soviet tanks patrolling the streets of Budapest in 1956 to put down the revolution (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Looking at the emergence of totalitarian regimes with Arendt urges us to reconsider how we understand politics and power. Hitler’s and Stalin’s regimes were no theoretical or academic phenomena (as “-ism” might suggest). Arendt was actually unhappy with her original publisher’s preferred title of The Origins of Totalitarianism, as it misleadingly suggests a causal development from a historical starting point, where she regards history not as a unstoppable chain of events but as a complex weave of actions and consequences. Arendt called the British edition of her book The Burden of Our Times, and the version she herself rewrote in German Elemente und Urpsrünge totaler Herrschaft (Elements and Origins of Total Domination).

This new political phenomenon was a moving target for Arendt. “Events are the only reliable teachers of political scientists. In this light we must check and enlarge our understanding of the totalitarian form of government,” Arendt writes in her reflections on the Hungarian revolution, and in the final section of Origins she notes: “It may even be that the true predicaments of our time will assume their authentic form—though not necessarily the cruelest—only when totalitarianism has become a thing of the past.”

LOA: Among Arendt’s more provocative conclusions concerns the totalitarian state’s creation of a “lying world of consistency,” a supreme fiction that supersedes the senses and positions the capricious whims of leaders as the law of the land. Can you unpack Arendt’s ideas about how totalitarianism distorts and remakes reality.

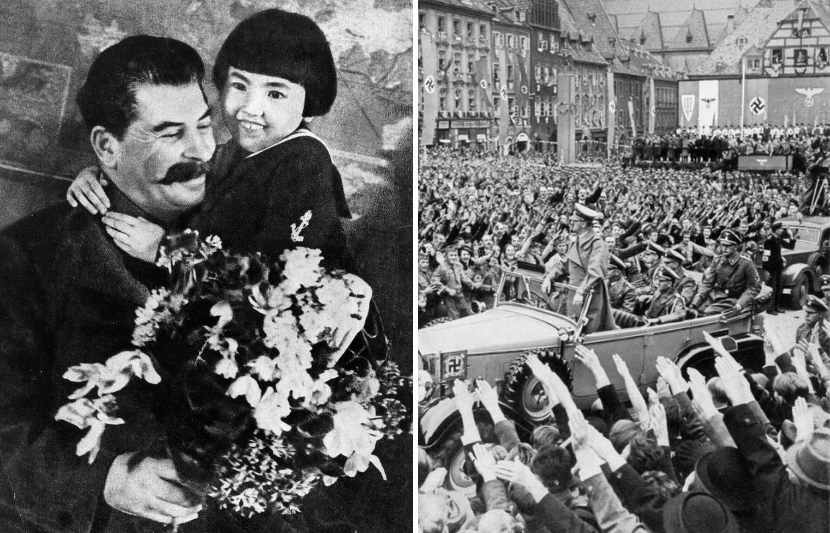

TW: For totalitarian regimes and leaders, the world with all its plural particles, its contradictions and complexities, is a threat and a source of disgust. Totalitarian ideology is determined to get rid of this mess of difference and plurality. It deduces the complexion of the world from one premise. In the case of Hitler’s Nazism, this is the dominance of the strongest race, i.e., the Aryan race, and hence the submission and abolishment of unfit races. In the case of Stalin’s communism, it is the creation of a classless society, i.e., the leveling of the possessing class.

These totalitarian regimes use terror to enforce their ideological, fictitious view of the world. Human beings are seen as material to shape this consistent world. Human dignity doesn’t count. Those who don’t fit are to be eliminated. People under totalitarian rule are pressured to approve lies that make the ideological picture of the world consistent, not contested. As Arendt puts it, if it is believed that only the greatness of the Aryan race or the brilliance of the Bolshevik system is capable of creating something as spectacular as, say, a subway, everyone who knows of the existence of the Paris subway is a potential threat.

1936 propaganda photo of Stalin embracing a child (Public Domain) and 1938 image of Hitler being driven through a crowd in Germany (CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

In other words, sheer factual reality can be and is a threat to a totalitarian regime that is set to unify all possible viewpoints into one consistent perspective. Dictatorships, alternatively, would not care much about varying perspectives as long as their political dominance isn’t seriously threatened.

We know this from archival research. Under Stalin, people scratched family members who were persecuted or deported out of family pictures in their home, afraid that regime inspectors might accuse them of connections to an “enemy of the state.” They manipulated and destroyed the manifest reality of the photograph to make it consistent with the totalitarian view.

Seen from the other side, this law of consistency seeks to eliminate what Arendt calls “the shock of reality”—the fact that something new, unexpected, and incomprehensible happens, something that might make you stop and think, that doesn’t fit into any preconceived notion.

The dark attraction that ideologies, full-blown totalitarian or milder versions, have is that consistency and perfection can also suggest cognitive strength (which is very different from what Arendt calls “thinking”). It rather resonates with “cold reasoning,” as Hitler put it. An alleged absence of “error” or unsettling “inconsistency” can be terribly seductive.

LOA: Complementing Arendt’s rigorous analysis is her vivid and distinctive prose. What stands out for you in Arendt’s language?

TW: This connects back to my previous point about “consistency.” The vividness of Arendt’s writing, I would say, celebrates and evokes the world in its plural fabric, just as poetry does. In her preface to Origins, Arendt addresses the challenge of actually understanding an unprecedented event such as the emergence of totalitarian rule. What is at stake in this attempt is, in Arendt’s words, “the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality—whatever it may be.”

What does “reality” mean here? I’d say at least three things: First, it is the facts that a historian, and we all, must acknowledge and record. Second, facts like the Nazi crimes against humanity, might be something we want to resist and not simply regard as “things that happen.” At the same time, this very reality might resist our urge to understand it, because nothing comparable has ever happened. Arendt urges us to embrace this “shock of reality”, i.e., to not subsume what is fundamentally new into existing categories and otherwise received knowledge.

Arendt’s ways of writing facilitate the experience of this openness between the world and language. She exposes language to the shock of reality and generates words that capture what is new to our world while keeping our reflections about it alive, just as other great poetic thinkers like Montaigne, Nietzsche, or Faulkner did.

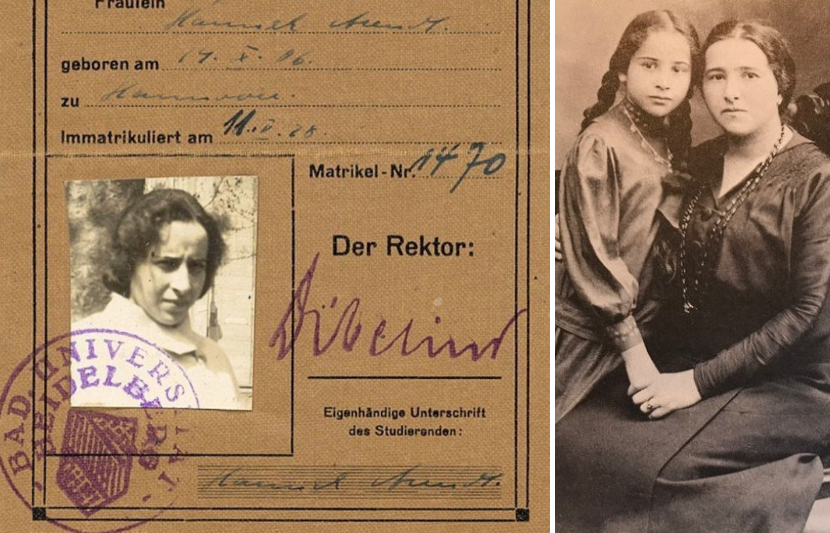

Arendt’s student card from Heidelberg University and Arendt with her mother at age eight (Public Domain)

LOA: Origins was Arendt’s first major book, published in 1951, a decade after she arrived in the United States as a refugee. What elements of Arendt’s biography come to bear in Origins?

TW: Arendt fled Germany early in 1933. Before that, she was arrested and interrogated by Nazi police after being caught collecting pamphlets of antisemitic hate speech on behalf a Jewish organization. She saw Jewish and non-Jewish friends persecuted, arrested, abused, and killed. She saw other friends and acquaintances falling in line with Hitler. In exile in Paris, she met refugees from all over Europe, many of them “stateless people” without a passport or state protection. After the Nazis invaded France in 1940, Arendt was interned at Camp Gurs. She would eventually escape and make it to the United States in 1941. All these elements of her personal experience resonate in the three parts of Origins: Antisemitism, Imperialism, Totalitarianism.

Right after Arendt had completed her manuscript of Origins, in late 1950, she noted a question into her Denktagebuch, or “Thinking Journals,” which inform the entirety of her work in the remaining twenty-five years of her life. “The question is:” Arendt wrote, “Is there a way of thinking that is not tyrannical?”

A response can be found in her book The Human Condition, where she also picked up a key thread coming out of Origins. Arendt’s deep dive into totalitarian rule made it clear that totalitarian regimes want to change human nature. As these regimes are determined to totally coordinate people’s behavior and thinking, they try to eliminate human spontaneity and therefore the basis of free action. The Human Condition takes the possibility seriously that such a threat, once it has entered the world, might never fully go away. Arendt argues—again in evocative and thought-provoking language—how human plurality and non-sovereign forms of “acting in concert” constitute what it means to be human: men, plural, not man, singular, live together on this earth.

LOA: In what ways are Arendt’s observations about Hitler’s and Stalin’s regimes relevant today, in our own political and cultural moment? At the same time, is there a danger in drawing overly neat parallels between the present and the history Arendt describes? How can we learn from her analysis without falling prey to simplified or tendentious comparisons?

TW: To me, a continuous inspiration and encouragement from Arendt’s work for any political moment, and today’s maybe in particular, is a commitment to look at the world with open eyes and senses, to not subsume everything new under what we believe we already know, to be careful and thoughtful with language, and to stay committed to communicative (rather than instrumental) notions of action.

Arendt in 1948 (National Endowment for the Humanities)

Arendt reminds us that a very effective form of action can simply be to say “no” and to simply not join. Of course, there are situations in which saying “no” and refusing to join are not exactly simple steps and might come with costs. Still, a gentle “no” or stepping aside can interrupt a chain that seemed unstoppable. A version of this is to resist preemptive obedience, to not comply in action or thought just because it seems unavoidable. These are typically not heroic acts but resemble spontaneous judgments, acts of common sense rather than overthinking. Arendt shares great examples of such small yet essential acts, often captured in anecdotes (not theories), in essays like “Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship” (1964), her collection Men in Dark Times (1968), or “On Violence” (1970), all of which will appear in a forthcoming LOA volume of Arendt’s collected essays.

Simply “applying” Arendt’s historical analysis of totalitarian rule to our current moment is something, in my view, that Arendt warns against. Her work might help us to see and name things, to make nuanced distinctions, to be cautious and courageous at the same time. But I understand her work to convey that we need to look at what is in front of us, and we need to think and speak for ourselves.

LOA: Arendt, an immigrant to the United States, was also a quintessentially American writer: a member of the New York literary scene, a friend of Mary McCarthy’s, and a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books. At the same time, she is a writer of global significance who, in many senses, belonged to the world. Can you talk about Arendt as both an American and an international figure of letters?

TW: We read Arendt as an American author because much of her work was written here, in English. In German-speaking countries, though, Arendt is being read as a German author, because she wrote in that language, too. Even scholars of Arendt often forget that she is a multilingual author. She herself wrote the majority of her books and essays in more than one language, in English and in German. Sometimes one language came first, sometimes the other. On closer examination, it is a fascinatingly generative back and forth between both. This actually is a quite cumbersome and time-consuming practice that Arendt could have forgone, like most other exiles—but she didn’t! I therefore read Arendt’s decision to think and write, on a daily basis, in a plurality of languages, as a committed response to the experience of totalitarianism. This multilingual complexion of Arendt’s thinking is made available for the very first time by a scholarly Critical Edition of Hannah Arendt’s Complete Works, for which I serve as general editor.

Arendt and Mary McCarthy in the 1960s (Library of Congress)

LOA: Origins opens with an epigraph from the German-Swiss philosopher Karl Jaspers, translated in the LOA edition as “Neither to fall prey to the past or the future depends on our being fully present.” Can you talk about the significance of this quote?

TW: Karl Jaspers was one of Arendt’s core mentors and dear friends, and he embodied for her the art of thinking together, in conversation. The epigraph captures that spirit; it’s lucid and opaque at the same time. It suggests wisdom and needs some further unpacking. It is incomplete like a phrase that might emerge from a conversation between friends. It’s like an aphorism whose meaning has to be activated and revived anew by each reader. Or it is like a letter that leaves something open, thereby inviting and welcoming a response. Here is a pulse of the present, mindful of the past and the future, but not controlled by them; a space in between for spontaneity, surprise, and, in dark times, to feel alive.

Arendt in 1975 (The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard)

Thomas Wild is Professor of German Studies and Literature at Bard College. He is the author of Hannah Arendt: Leben, Werk, Wirkung, and is General Editor of the Critical Edition of the Complete Works of Hannah Arendt. He co-edited the LOA edition of Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism, Expanded Edition with Jerome Kohn, and he will edit the forthcoming volumes in LOA’s Arendt series.