Tom Lehrer performing in Copenhagen, 1967 (Public Domain)

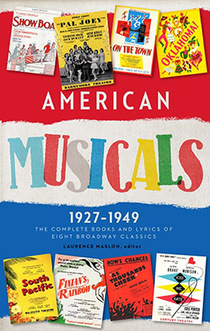

American humor lost one of its great voices this summer with the death of genius singer-satirist Tom Lehrer at the age of ninety-seven. The mind behind such madcap classics as “We Will All Go Together When We Go” (“When the air becomes uraneous / We will all go simultaneous”) and “Wernher Von Braun” (“‘Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down? / That’s not my department,’ says Wernher von Braun”), Lehrer was also an “advisor without portfolio” for the two-volume Library of America edition of American Musicals, edited by Laurence Maslon. Below, we present Maslon’s reflections on his correspondence with the legendary That Was the Week That Was songwriter during the selection process for American Musicals, revealing a collaborator at once hilarious, perceptive, and erudite.

By Laurence Maslon

As the adage goes, you should never meet your heroes. But what if you e-mailed them?

In summer of 2007, I was working on a multi-part PBS documentary with producer/director Michael Kantor entitled Make ’Em Laugh: The Funny Business of America. One episode was devoted to satire and parody, and an essential component of that story would have to be Tom Lehrer. Lehrer’s catalogue of satirical songs from the 1950s and ’60s (less than three dozen examples) was an outsized influence on the minds of deranged delinquents of my generation; if you could be an anarchist and still have a hero, he was our hero. We tracked Mr. Lehrer down via his e-mail address at UC Santa Cruz (livinglegend@ucsc.edu), where he was, then, a professor in both mathematics and musical theater history. Professor Lehrer’s response to a request for an on-camera interview was both concise and, er, pointed: “I’d rather have steel spikes driven through my eyes.”

Perhaps the adage was true after all.

Five years later, I was the editor for the first collection of American musical theater texts to be published by Library of America. To collate and organize the book and lyrics (librettos) of beloved stage pieces over a (then) ninety-year performance history was a complicated task, especially as it involved separating out the subjective (musicals that I love) from the objective (musicals that other people love). I was tasked by LOA president and publisher Max Rudin to trawl among other experts in the field to acquire their subjective and objective choices; a kind of informal editorial advisory board. It seemed a good opportunity to reach out to Tom Lehrer again. His aversion (perhaps not strong enough a word—maybe “abomination” is more fitting) to personal promotion was now well known to me, but perhaps getting him to weigh in on something he loved—such as American musicals—rather than on a subject he found ponderous—himself—would be a different story.

The second time was the charm.

I had by then established some cred with Lehrer, having taught drama for a summer semester at Santa Cruz, and he responded if not with alacrity at least with relative enthusiasm. And so began an e-mail correspondence about which sixteen musicals should enter the hallowed canon of the Library of America.

Initially, for reasons I can’t now remember, there was a discussion about taxonomy, i.e., how the various musicals would be categorized and in what volumes. I suggested there might be a “Groundbreakers” volume and a “Classics” volume—and furthermore that the volumes would cover musicals from 1927 (Show Boat) to the present. Lehrer tried to wrap his mind (and arms) around this muddle:

I expect that your rubrics “Classic” and “Groundbreaker” are tentative, but I do think they’re a tad strong. “Historic” or “Landmark” are probably also too much and “Great” too obvious, but I’m sure you will come up with something. I like 1776, but I don’t consider it a “groundbreaker.” [Author’s note: 1776 was the first musical I ever saw—and one of my favorites—and it was always going to make my “cut.”] I would eliminate RENT as well, on the grounds that it is too early to tell. I didn’t notice a wave of rock musicals following in its wake. Remember what happened with HAIR, which may be occasionally revived (like now) but which led to nothing.

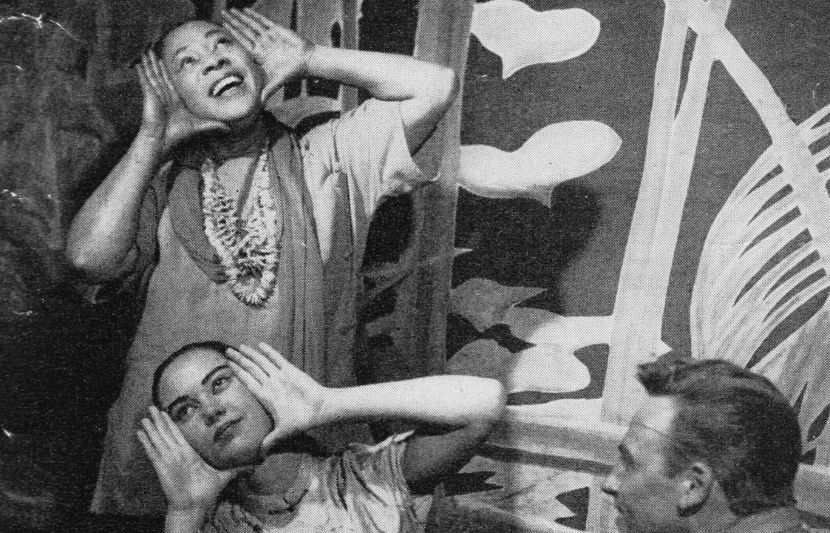

For some reason (which, again, I can’t quite recall), I had trouble navigating with various texts by Rodgers and Hammerstein: some were “groundbreaking” (Oklahoma!); some were “classics” (South Pacific); some were beloved by their creators (Carousel); some were beloved by audiences but not by me (The King and I, The Sound of Music). I seem to remember putting the thumb on the scale of South Pacific, partly because of its compassionate treatment of racial discrimination (which fit into some of the volumes’ larger themes), rather than Oklahoma!. Here’s Lehrer on that topic:

How can one deny that OKLAHOMA! was TRULY a “groundbreaker” while SOUTH PACIFIC, though undeniably a “classic,” was not?

Perhaps you have been seduced by the one-minute song “Carefully Taught”—the only song in the score which refers at all to the race question, by the way. One problem in considering SP groundbreaking (though it is definitely a classic) is the evasion of the larger problem. If Liat had been Melanesian (i.e., black) the show wouldn’t have gotten past the first backers’ audition. Tonkinese is just white enough not to offend most Broadway audiences but not white enough to avoid controversy elsewhere. The tipoff for me has always been Emile’s line: “I want you to know I have no apologies. I came here as a young man. I lived as I could.” Now if that’s not an apology, I don’t know what is. (It’s irrelevant to the show, of course, but we all know the Michener version of Emile’s prior love life, certainly inappropriate for Broadway.)

And if you really and truly consider OKLAHOMA! neither a “classic” nor a “groundbreaker,” at the very least you should include it in Volume Two. (You don’t have it on ANY of your lists! For shame!)

Still from South Pacific souvenir program, 1950 (Public Domain)

In the end, dear reader, both Oklahoma! and South Pacific went into Volume One—a choice made somewhat easier by the eventual decision to organize the volumes chronologically. Lehrer plumped for some straight-out musical comedies of the 1960s, such as Neil Simon’s Little Me, and made an impassioned case for Bock and Harnick’s 1963 She Loves Me, which he considered the “perfect musical,” but he didn’t have much truck with shows past the mid-1970s:

I would consider these volumes to be a historic anthology, and the attempt to make it chronological merely points up the paucity of great musicals in the past 30 years. Only THE PRODUCERS and RENT are in that time frame, and I wouldn’t consider either of them a great musical. (By the way, I wonder if LOA would let you keep the line, “Who do you have to fuck to get a break in this town?”—an old line which I never found funny.)

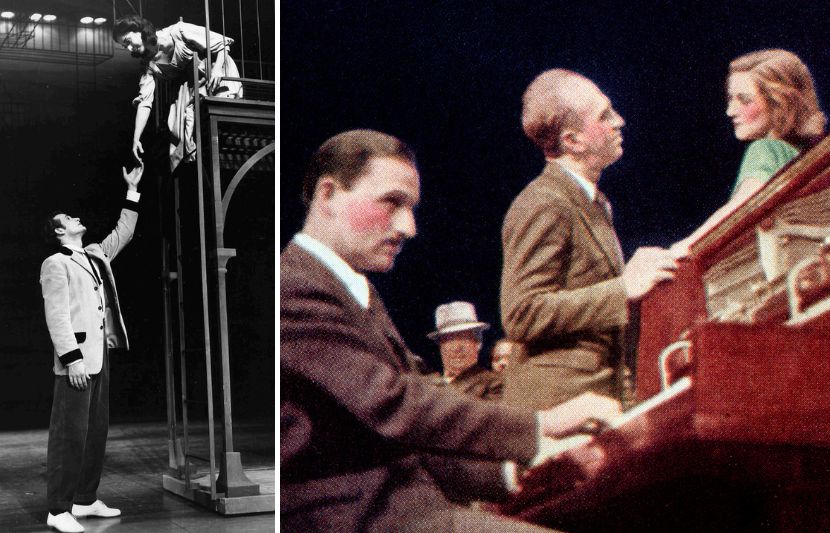

Lehrer and I had a strong disagreement about West Side Story. Although undeniably a stage “classic” (the “legs” of which are still going strong), I felt that by far the major strengths of West Side Story were its music and choreography, as opposed to its book and its lyrics, which the reader would be stuck with, uneasy in their easy chair. Lehrer:

I would definitely include WEST SIDE STORY in the “classic” list. A truly fine book and great lyrics. You seem to exclude it because the music is too good, but to me that’s like penalizing an A student in English because he also got an A in math.

We went back and forth over several months and multiple e-mails. I’ll admit that occasionally I’d run something up the flagpole just to get a reaction out of him. I had chosen a revue (i.e., a non-narrative show) by Moss Hart and Irving Berlin from 1933 called As Thousands Cheer because I thought it was the best example of a robust genre (and had never been published). Lehrer wagged a virtual finger at me: “Not having read the sketches, I can’t argue the point, but they’d better be pretty darn good!”

Original stage productions of West Side Story (1957) and The Cradle Will Rock (1937)

Our most intense divergence revolved around The Cradle Will Rock, Marc Blitzstein’s political musical from 1937. For theater historians, it was a no-brainer: it captured Depression-era musicals better than any other; it was directed by Orson Welles; and, as it was shut down by the federal government for being too provocative, it was a piece of American history (it was also not in print). For Professor Lehrer, a gentle satirist if ever there was one, this was all too much:

THE CRADLE WILL ROCK: I do not see how this can possibly be called a classic. It was a flop show, which has never had a major revival. It had NOT ONE MEMORABLE SONG (nor lyric, for that matter)—I have most of the original sheet music as Exhibit A—and a simplistic, agitprop cartoon of a book. But perhaps I’m being too easy on it.

In the end, The Cradle Will Rock didn’t make it into the American Musicals set. Whether or not it was for space reasons or tortuous Solomonic decision-making (it’s never easy to do an anthology. . . ) or whether I could not bear to cross a beloved hero (that’s some cross to bear), I can’t really say. I will say that Lehrer got the point for an American musicals publication (one volume or two) right off the bat, which was immensely gratifying:

I really like the idea of such a volume, whether or not there is a second. I should think LOA would go for the idea that this “art form” is an important part of American cultural history, so this volume would add a certain academic patina, apart from its entertainment value.

The two-volume American Musicals was released by Library of America in 2014 and, along the way, it gave me the opportunity to lock horns with my most dyspeptic hero (well, there was Sondheim, but that’s another story). It was a contentious couple of months, but as Lehrer himself wrote, in “National Brotherhood Week”: “be grateful that it doesn’t last all year.”

Signed portrait of Lehrer in 1958 (Public Domain)

Laurence Maslon is editor of American Musicals (1927-1969), a two-volume set of sixteen musicals, as well as the editor of Kaufman & Co.: Broadway Comedies (which includes Of Thee I Sing, a recommendation of Tom Lehrer’s), published by LOA in 2004. Maslon’s most recent book is Hitchcocktails: Lethal Libations Inspired by the Master of Suspense (Insight Editions).