Flannery O’Connor is a timeless and arresting chronicler of the American South: its attitudes and landscapes, its vernacular and history, and perhaps most importantly its profound and multifaceted relationship to religion and the divine. To celebrate what would have been her 100th birthday this year in 2025, we share this essay from Library of America contributing editor James Gibbons on one of O’Connor’s greatest stories, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” from her 1955 collection of the same name and included in LOA’s volume of O’Connor’s collected works.

by James Gibbons

The story begins innocuously enough in a living room in Atlanta. A wound-up grandmother harangues her family about a serial killer reportedly on his way to Florida, where, despite her protestations and her wish to visit relatives in east Tennessee, the family is headed the following day. Her son Bailey ignores her as best he can from behind the sports page. The grandchildren mock her in a tone of teasing, irritated tolerance. The elderly woman’s daughter-in-law is introduced, in a typical O’Connor gesture, as merely “the children’s mother,” pointing up longstanding divisions within the family: such a begrudging acknowledgment neatly telegraphs a history of chilliness between Bailey’s wife and her mother-in-law.

We are seemingly in the realm of lightly satiric, homespun family comedy, and this impression is reinforced when the group sets off on its journey. The supposedly reluctant grandmother installs herself in the car well before anyone else, takes pedantic note of the odometer mileage, and hides her cat in a basket beneath the front seat “because he would miss her too much and she was afraid he might brush against one of the gas burners and accidentally asphyxiate himself.”

It would appear that we are being led by a wry, sophisticated humorist who foregrounds the foibles of her characters—patently her lessers—in a gently chiding tableau. That these characters are from the South, with its well-known picturesque idiosyncrasies and long tradition of anecdotal, local-color fiction, makes it even easier for us to feel we know the general direction the story is heading.

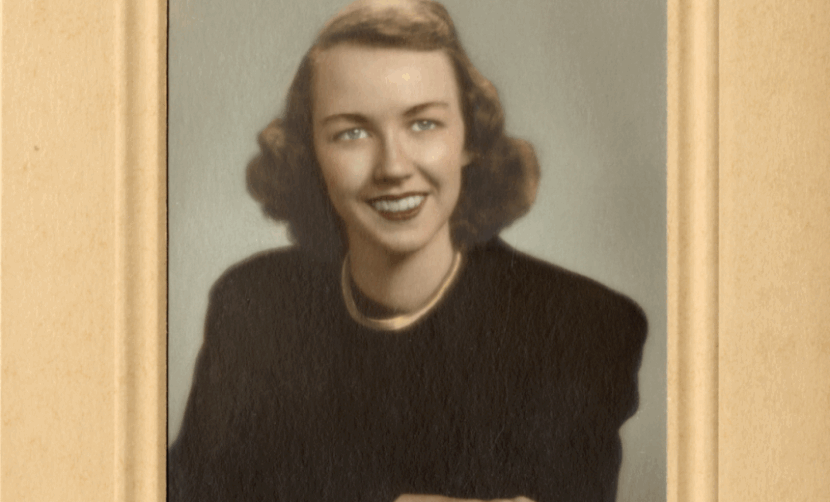

Photograph of Flannery O’Connor from 1947 (Georgia College & State University / Flannery O’Connor Institute for the Humanities)

The opening paragraphs, if we knew nothing about Flannery O’Connor, suggest we are reading a sort of southern-fried James Thurber, and this would be a reasonable assumption: as an undergraduate at Georgia State College for Women, O’Connor was a gifted graphic artist who worked seriously at her cartoons and aspired to become as popular and successful a cartoonist as Thurber had become at The New Yorker. It’s an intriguing thought experiment to speculate about the work O’Connor would have produced had she followed this career path rather than going off as a graduate student to the University of Iowa, enrolling first in journalism and soon afterwards in the Writers Workshop there; all the same, given the depths she plumbed in her fiction and the intricate paradoxes she explored, it’s hard to imagine that she would have been able to achieve the same scope.

The car turns onto a dirt road and, shockingly, this antiquated notion of the gothic yields to a contemporary gothic scene—one that is austere, malevolent, and terrifying.

Soon the slice-of-life Georgia comedy begins to absorb other elements. It takes up tropes and themes that evoke different registers than the humorist’s winking knowingness. O’Connor gives us a hint of lyricism when she describes “the brilliant clay banks slightly streaked with purple; and the various crops that made rows of green lace-work on the ground” and notes how “the trees were full of silver-white sunlight and the meanest of them sparkled.” And the grandmother’s offhand observations and spells of nostalgia seem more pointed than they might be were she just a bearer of colorful eccentricities, a risible figure of fun.

Receptive to the lament of the restauranteur Red Sammy that “a good man is hard to find” in a world where serial killers run free and “Europe was entirely to blame for the way things were now,” the grandmother indulges fantasies of an airbrushed Southern past. She sees a Black child standing in the doorway of a shack and effuses, “If I could paint, I’d paint that picture.” A graveyard on an old plantation brings to her mind—inevitably, though jokingly—Gone With the Wind. Through the grandmother’s silly clichés and reflexive mental associations, O’Connor holds up to scrutiny the sentimentalized myths of the Southern past, those kitschy reveries that for many had stood in for the region’s conflicts and muffled their horrors in gauzy ribbons of feeling.

So when the family makes their fatal turn off the highway, it is to see a plantation house rumored to have hidden within it a cache of silver, a trove that somehow Sherman’s plundering armies passed over—a romantic fantasy, and one that the grandmother freely embellishes when she claims that the house has secret panels within it as well. The car turns onto a dirt road and, shockingly, this antiquated notion of the gothic yields to a contemporary gothic scene—one that is austere, malevolent, and terrifying.

Listen: Flannery O’Connor Reads “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” in 1959

Of course there is no grand estate house—not in Georgia, anyway—and what the grandmother and her family discover along the dirt road, after their car falls in a ditch and the children delightedly call out “we’ve had an ACCIDENT,” is the serial killer, the Misfit, whom the grandmother has been preoccupied with since the story’s opening paragraph.

Although O’Connor—in the spirit of Chekhov’s famous dictum about the onstage gun needing to go off—has prepared us for the appearance of the Misfit, in a more profound sense she has radically rewritten the rules that seemed to have governed her tale. The effect is dizzying, and intensifies when it becomes obvious that the family can only be murdered by the Misfit and his men.

The grandmother reached up to adjust her hat brim as if she were going off into the woods with him but it came off in her hand. She stood staring at it and after a second she let it fall on the ground. Hiram pulled Bailey up by the arm as if he were assisting an old man. John Wesley caught hold of his father’s hand and Bobby Lee followed. They went off toward the woods and just as they reached the dark edge, Bailey turned and supporting himself against a gray naked pine trunk, he shouted, “I’ll be back in a minute, Mamma, wait on me!”

That most of the killing takes place on the story’s peripheries suggests the decorum of classical tragedy and imbues the episode with an eerie, discomfiting gravitas. And despite their plain speech the Misfit and the grandmother are having what is, at its core, a theological discussion.

“If you would pray,” the old lady said, “Jesus would help you.”

“That’s right,” The Misfit said.

“Well then, why don’t you pray?” she asked trembling with delight suddenly.

“I don’t want no hep,” he said. “I’m doing all right by myself.”

As readers the ground has shifted beneath us, and we now brush up against questions that we hadn’t expected to face when this humbly flawed, ordinary family set out on their road trip—questions about mercy, punishment, and justice, and the inscrutable ways of God. For in what sense could these people deserve what is happening to them? And if we may have wished, as the grandmother prattled on about how things in the past had been so much better, to see her given her comeuppance, was this the sort of fate we’d ever have imagined for her?

We have left the world of the humorist far behind, yet the comedy remains—O’Connor’s humor can be as black as Goya’s in Los Caprichos, but she also had a fabulous ear and a sense of timing a Hollywood screenwriter would envy. Her darkly funny, violent world continues to exert tremendous appeal—and fascination—not least because of its collision of incongruous elements: the low and the transcendent, the comic and the speculative, the grotesque and the divine. In her meticulously crafted fiction, these opposites resolve via the unlikely transmutations and orderings of the creative act. For within her peculiarly personalized spiritual orthodoxy, ultimately nothing is incongruous; all is one. As she wrote, quoting the French theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, “Everything that rises must converge.”