From Margaret Fuller: Collected Writings

In late 1844 Fuller accepted an offer from Horace Greeley to become a columnist for the New-York Tribune; of the more than 250 pieces Fuller wrote over the next two years, a good number were investigations of the plight and treatment of the city’s underclass. Soon after her arrival in New York, she wrote to a friend, “I do not expect to do much, practically, for the suffering, but having such an organ of expression as the Tribune, any suggestions that are well grounded may be of use.”

A remarkable series of columns chronicled Fuller’s excursions to the various hospitals, prisons, and poorhouses of New York City and its environs. In October 1844 Fuller went to Sing Sing prison to meet with women who had been incarcerated for prostitution and public drunkenness. She returned to the facility on Christmas Day and spoke at the services held in the prison’s chapel; her column about the holiday excursion solicited funds to help women prisoners. This appeal and her other fundraising efforts on behalf of the Women’s Prison Association helped bring about the establishment during the following summer of the Home for Discharged Female Convicts—perhaps the world’s first halfway house for women.

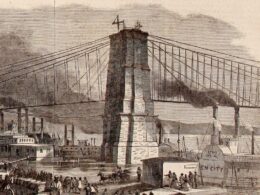

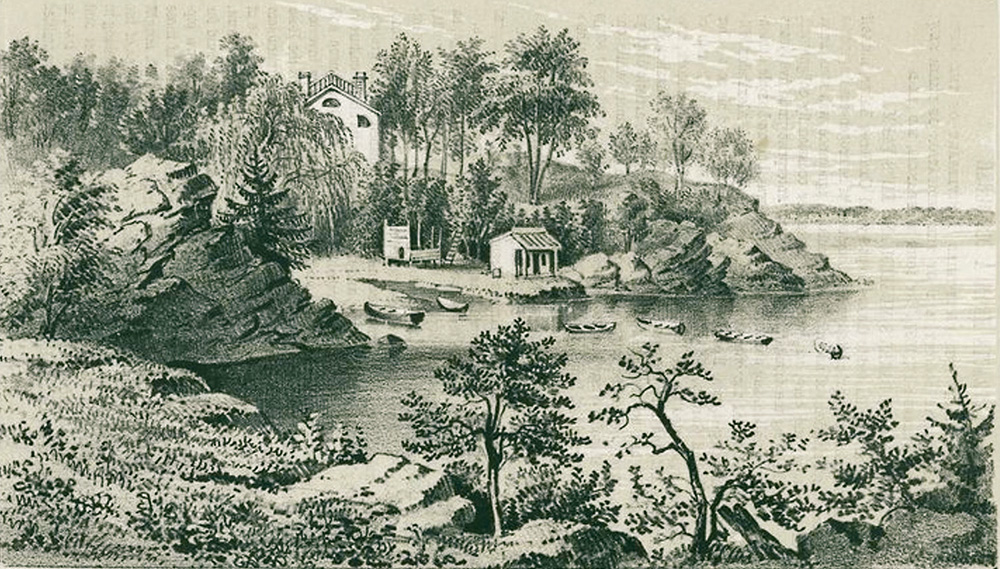

Another column detailed in mostly positive terms Fuller’s visit in February 1845 to the new Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane. (The commendable conditions did not last, alas; within a decade, the asylum had become a notoriously underfunded dumping ground for disorderly residents.) A month later, in March, she described, with increasing displeasure, her trips to the poorhouse at Bellevue, to a “farm school” for orphans and children from impoverished families, and to a new asylum and the new penitentiary, both on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island).

She used her column, too, to describe how her fellow citizens behaved to those less fortunate. One day, when she took the ferry to work, she attempted to come to the assistance of a young boy who was traveling with an infant but was interrupted by a bullying “well-dressed woman” who loudly harangued the boy, to no apparent purpose, for being on the boat. In a column condemning the “Prevalent Idea That Politeness Is Too Great a Luxury to Be Given to the Poor,” she used the incident to disparage the officious intervention that often passed for do-goodism among the rich.

You can read that column at our Story of the Week site, along with an introduction describing how her mentor and close friend Ralph Waldo Emerson thought her newspaper work, while good, was nevertheless beneath her talents.