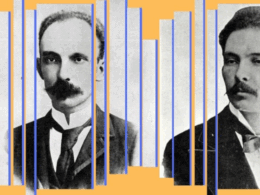

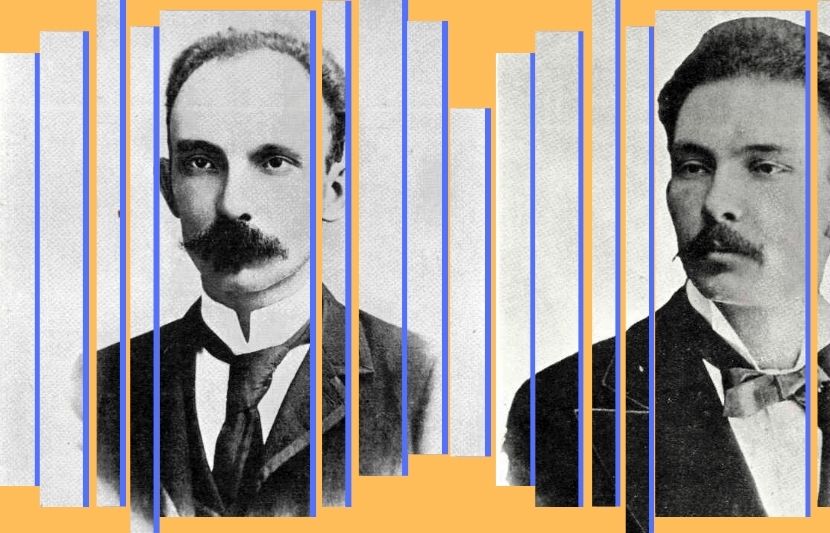

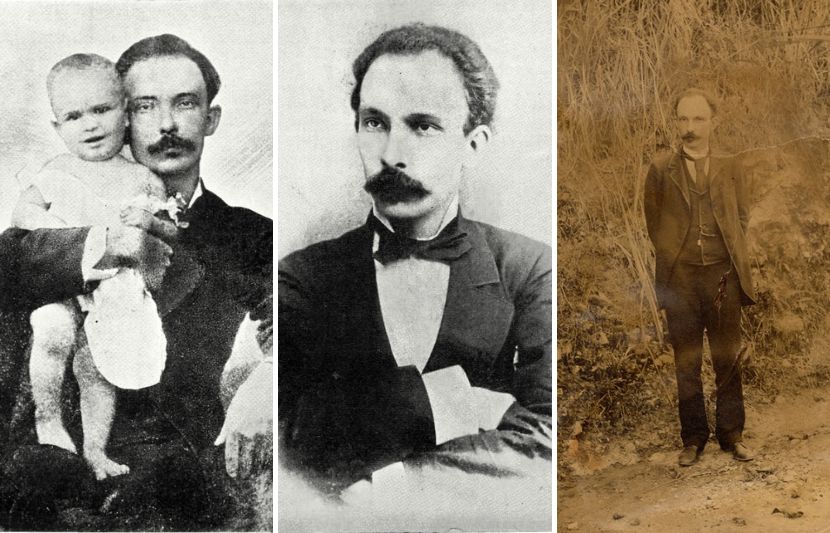

Portraits of José Martí in 1892 and 1875 (Public Domain)

José Martí is among Latin America’s most influential poetic and political voices. Exiled as a teenager from his native Cuba, he spent years producing an outpouring of poetry, essays, and journalism in New York City before returning to his homeland to join the revolution then unfolding against the Spanish colonists. Killed in battle 130 years ago this May, his legend lives on, not just in innumerable memorials and statues honoring his legacy across the Spanish-speaking world, but in his astounding, vital poetry, selections of which appear in Library of America’s Latino Poetry anthology.

Below, public humanities fellow Susana Plotts-Pineda explores the astonishing life and electrifying verse of this incomparable poet-warrior, whose words and actions continue to reverberate more than a century after his death.

On May 19, 1895, Cuban poet and revolutionary José Martí was killed fighting Spanish colonial troops at the Battle of Dos Ríos near the confluence of the Cauto and Contramaestre rivers. Hastily buried in a mass grave, he was later disinterred and sent to Santiago de Cuba for burial.

Just four years prior he had described a vision of this end in one of the plainspoken and dazzling autobiographical poems that comprise his 1891 Simple Verses (the first of which appears in Latino Poetry: The Library of America Anthology):

I wish to leave this world

In the most natural way.

So in a bed of leaves

Let them carry me away.

His death in combat has elevated the poet to martyr status in the pantheon of Cuban historical memory and inspired its own artistic outpouring. In his own poem in the Latino Poetry anthology, “Flowers and Bullets,” Martín Espada writes of the “poet shot from a white horse in his first battle,” musing that if he were to die, let it be as Martí did, with a heart filled with flowers and bullets.

Illustration of Martí’s death from 1925 (CC0) and Martí’s mausoleum (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Considered among Latin America’s major poets and intellectuals, and a foundational figure of the first uniquely Latin American literary movement, Modernismo, Martí was born in Havana on January 28, 1853. Stirred from an early age by the struggle for Cuban independence from the Spanish, he was sent to prison at sixteen. After his sentence was commuted to exile in Spain, he spent a major part of his life away from his homeland, first in France, then Mexico, Guatemala, Venezuela, and the United States.

Although Martí was fervently active as a diplomat, publisher, and political organizer, and prolific as a writer throughout his life, it was in the United States—and specifically in New York, where he lived from 1881 to the year of his death—that he produced the greater part of his oeuvre.

Known for his poetry, political essays, and letters, Martí is also credited for approaching journalism as a literary form through a distinctly personal style, leaving a lasting influence on the genre. Scholar and translator Anne Fountain, whose translation of Simple Verses appears in Latino Poetry, writes: “Gleaning material from U.S. newspapers and journals, he absorbed stories and news reports and recast them, sometimes in beautifully rendered translations and often in paraphrases mixed with commentary.” His Escenas Americanas shaped Latin America’s perceptions of its neighbor to the north in ways that have been compared to the influence of Alexis de Toqueville’s Democracy in America on Europeans.

He wrote regular columns for American and Latin American newspapers, notably in Mexico’s El Partido Liberal and Argentina’s La Nación. These chronicles, or crónicas, became paradigmatic of his style, where he documented his experience of modern, everyday life in America while tackling the larger social issues that consumed him.

Pages from the first edition of Martí’s Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) (University of Florida)

Early on, Martí was fascinated by America and its multitudes, in which he saw reflected the unique character of its people, their exemplary work ethic, and the possibilities open to anyone with the ingenuity to seize them. Writing for the New York weekly literary magazine The Hour, he notes: “One can breathe freely, freedom being here the foundation, the shield, the essence of life. . . . A good idea finds always here suitable, soft, grateful ground. You must be intelligent; that is all.”1

Martí was amazed at the standard of living Americans had achieved in such a short span of time, positing that the United States’ historical trajectory could offer a model for nascent Latin American nations. He believed that it was by acting in accordance with their unique character or “soul” that nations could become truly free.

At the same time, his writings became increasingly marked by descriptions of the great inequalities of the Gilded Age in New York, the outsized influence of an elite class and its drive for international profiteering, the apolitical and materialistic nature of its citizenry, and the “carnival atmosphere” of American politics. He condemned American racism toward Black Americans, Native Americans, and those in neighboring nations to the south. Most of all, he demonstrated a deep wariness of what U.S. imperial designs would mean for Latin America, articulating a perennial commitment to decolonization and national self-determination.

In his essay “Our América,” he presciently describes the specters of what would come to haunt the twentieth century:

The soul, equal and eternal, emanates from bodies that are diverse in form and color. Anyone who promotes and disseminates opposition or hatred among races is committing a sin against humanity. But within the jumble of peoples that lives in close proximity to our peoples, certain peculiar and dynamic characteristics are condensed—ideas and habits of expansion, acquisition, vanity, and greed—that could, in a period of internal disorder or precipitation of the nation’s cumulative character, cease to be latent national preoccupations and become a serious threat to the neighboring, isolated, and weak lands that the strong country declares to be perishable and inferior.2

During his time in the United States, Martí also translated and reviewed the work of American writers he admired, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Helen Hunt Jackson, and Walt Whitman, significantly expanding their reach among Latin American readers. He became enthralled with Whitman after he witnessed the poet’s 1887 lecture on Abraham Lincoln, writing in his essay “El poeta Walt Whitman”: “Only the holy books of antiquity offer teachings that are comparable in their prophetic language and robust poetry to the grand and priestly apothegms that this old poet emits like gulps of light.”3 For Martí, Whitman reflected his vision of poetic boundlessness and multivocality; he was “of all classes, creeds and professions,” finding in each “justice and poetry.”

In his verses, the struggle of matter to be, to pass from darkness to light and back again, is expressed through a constant process of mirroring, dappling, and ultimately becoming, like the image in his prologue of waves crashing in the dark, succeeded immediately by bees foraging for pollen.

Although Martí lauded Whitman’s embodiment of his poetic and social ideals, establishing what became known as the “cult of Whitman” in Latin America through his 1887 essay, his writings also gave way to a wave of complex, not always favorable discourse on the poet among Latin American intellectuals. Because of the open-endedness of his works, which welcome multiple readings, Whitman could represent both the embrace of a humanistic plurality that marked revolutionary aspirations in the Americas while also allegorizing the figure of a towering imperial North. In this way, Whitman mirrored for Latin American writers Martí’s own ambivalent relationship to the United States.

Martí’s use of common, direct speech as well as his increasing anxiety about the threat America posed to Cuba in a post-colonial order emerge vividly in Simple Verses. The poems were penned while Martí was recuperating, on doctor’s orders, in the Catskill Mountains after attending the first Inter-American Conference (1889–90), where a U.S. plan to purchase Cuba emerged. In his prologue to the book, which opens with the same intimacy that marks the poems—“My friends know how deeply these verses spring from my heart”—Martí describes his “winter of anguish” when “the Spanish American nations gathered in Washington, under the shield of the fearsome eagle,” expounding on the “horror and shame at the thought that we Cubans might—in a parricidal gesture—support a senseless plan to partition Cuba.”4

In the Catskills however, “streams flowed and clouds gathered in upon themselves, and I wrote verses. At times the sea roars and waves crash, in the black of night, against the rocks of a bloodied castle: at times a bee hums as it forages through the flowers.”

Photos of Martí in 1880 (pictured with son José Francisco), 1885, and 1892 (Public Domain)

In these exalted, simple poems, he fluidly melds the personal and political; concerns which, in his life, were so indelibly wedded converge in his lines like overlapping waves–metaphors for one another. The poems and their prologue are marked by the anguish he describes, but also profound gratitude toward his friends. Political struggle is interwoven with the necessity of friendship and carried through with the conviction of plain forms: “I am bringing these verses to press because, thanks to the endearing and enthusiastic reception given them by some good-hearted souls in an evening of poetry and friendship, they have already been made public. And because I love simplicity and believe in the need to express sentiment plainly and sincerely.”

Simple Verses attests to the formative years and experiences of the poet, but also to the birth of political consciousness as an organic, collective process, springing from an “I” that, like Whitman’s, extends past the speaker, to embrace the other and the panoramic sweep of all embodied experience.

The “I” here is foremost an “I” of friendship in both an intimate and expansive sense: an “I” that connects a speaker to a reader, a citizen to a multitude, and individual human perception to a protean, instantiating, and continuously affirmed reality encompassing all of life. Martí’s “I” is both the observer and the world he observes:

No boundaries bind my heart

I belong to every land:

I am art among art,

A peak among peaks I stand.

The poems cover Martí’s early, transformative memory of watching slave ships arrive in Havana (slavery is described elsewhere in the verses as “man’s most terrible shame”) as much as they express his belief in the ever-renewing, parallel processes of life and death of which the individual life is just a fragment:

I know that when life must yield

And lead us to restful dreams

That alongside the silent field

Is the murmur of gentle streams.

Martí’s “I,” exemplifying a fragmented vision of modern selfhood present in the work of contemporaries from Baudelaire to Whitman, is uniquely shaped and energized by the specific historical circumstances of decolonization:

My heart holds anguish and pains

From a wound which festers and cries

The son of a people in chains

Lives for them, hushes, and dies.

Here and elsewhere in Martí’s work lies the sense that birth is the selfsame expression of the creative act and of revolution. In his own personal bonds—reflected in the poems he wrote to his son in Ismaelillo (“I am son of my son!”)—he saw the expression of a cyclical, creative universe and of revolutionary potential. Revolution as a means of attaining freedom, equality, and dignity for man could be the fruit of the cosmos as much as something carried out by a people (or rather, these were one and the same):

Beneath me I hear a sigh

From the slumber of earth and sea.

But in truth it’s the morning’s cry

Of my son who awakens me.

In his verses, the struggle of matter to be, to pass from darkness to light and back again, is expressed through a constant process of mirroring, dappling, and ultimately becoming, like the image in his prologue of waves crashing in the dark, succeeded immediately by bees foraging for pollen. Here is the sense that history, in its constant flux, in its struggle, reflects the struggle of matter itself: what becomes is beautiful in its potential for transformation and, in its beauty, just:

All is lovely and right

All is reason and song

Before the diamond is bright

Its night of carbon is long.

The year after writing Simple Verses marked a turning point for Martí. He would devote the short remainder of his life to revolutionary activity, helping to found and lead the Cuban Revolutionary Party, drawing out plans for an invasion alongside revolutionary leader Máximo Gómez, and then dying just seven years shy of Cuba’s independence from Spain.

Mural of Martí in Havana, Cuba (CC BY 2.0)

By way of the song “Guantanamera,” which borrows some of Martí’s verses and melds them with a popular Cuban guajira, the poet’s words have been translated and sung throughout the world. American songwriter Pete Seeger, who coincidentally first encountered the song in the Catskills and then translated and introduced it into his repertoire, wrote in his memoir: “Martí’s philosophic verses have ennobled the old melody. . . . I’ve sung it in 35 countries on four continents; it rings true in every one.”

This feels apt for Martí, for whom revolutionary struggle—his life’s work—was fundamentally undergirded by love, and specifically friendship, a theme that appears repeatedly in the verses and unites the moment of writing while convalescing in the Catskills to that of his death in battle.

Friendship as a foundation for poetry has a long history, and was central, for example, to the New York School: Frank O’Hara, somewhat wryly, described the poem’s place as between “two persons instead of two pages” and gestured to its interchangeability with a phone call. In reading Martí’s verses and beholding their profound, plainspoken intimacy, one comes to feel the poet’s voice as a kind of presence. In them, he writes of a “dead friend who comes / to visit me sometimes,” singing “like a two-winged bird”—not so different than a pigeon that might occasionally land on the head of his likeness, riding a rearing bronze horse on Central Park South just two blocks from Library of America’s office.

Statue of Martí in New York’s Central Park (Central Park Conservancy)

Footnotes

1 Martí, José. “Impressions of America.” Selected Writings. Translated by Esther Allen, Penguin Books, 2002.

2 Martí, José. “Our América.” Selected Writings. Translated by Esther Allen, Penguin Books, 2002.

3 Raab, Josef. “El gran viejo: Walt Whitman in Latin America.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 3, issue 2, 2001, https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1122

4 Martí, José. Versos Sencillos / Simple Verses. Translated by Anne Fountain, McFarland, 2005.