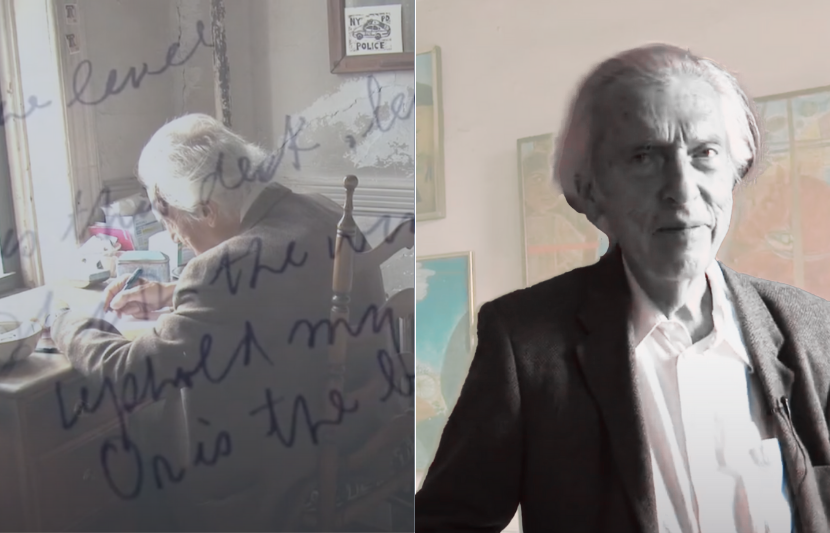

Photo illustration with still images from “Samuel, the Concise Poet,” Know Your Neighbor, WNYC, 2009.

Inklings

Inklings sans ink

Cling to the dry

Point of the pen

Whose stem I mouth

Not knowing when

The truth will out

From his three-bedroom cold-water 39-dollar-a-month apartment in New York City where he lived alone with a grapefruit tree for more than fifty years, Samuel Menashe composed short, mystifying poems of astonishing depth and power. Today, September 16, would have been his hundredth birthday.

In the space of just three or four lines and a few dozen syllables, Menashe could tumble and compress language into gemlike compositions that, on the one hand, recall mesmerizing, magic incantations and, on the other, the cryptic muttered utterances of the autochthonous urbanite, staring out his tenement window at the pulsing street life outside. Brevity was no crutch for Menashe’s art. “The shorter they are,” wrote The Guardian of his poems, “the more there is to say about them.”

For years, those with the most to say about Menashe were British and Irish; his collections would appear to acclaim in the UK while remaining unpublished and largely unread in the United States. Unaffiliated with any particular poetic school or movement, Menashe nested at the margins of the American literary world and found integrity in isolation. “For him to be a self-affiliated bohemian bachelor poet was his only chance for poetic truth,” writes critic Nicholas Birns, “and his desperate venture a high-risk gamble that, in the fullness of time, paid off.”

‘The struggle is against too many words!’ he declares from the couch in his cozy, cluttered Greenwich Village apartment.

That payoff came in 2004, when Menashe, age eighty, received the first “Neglected Masters Award” from the Poetry Foundation, followed by publication of New and Selected Poems by Library of America. In his introduction to the volume, editor Christopher Ricks supplied this statement from Menashe, originally sent to his UK publisher Victor Galancz to explain his creative motives: “I do not try to prove myself by inventiveness. What is does not need to furnish proofs. Nor will I demonstrate my modern involvement by howling or expressing the complexity of my thought. I will not increase the noise.”

What prevails in the poems of Menashe, who died in 2011, is indeed a kind of dense, reverberating silence, brought about by the sparsity of his language and the vastness of his pages’ whitespace. By not increasing the noise he instead focuses his attention on crystallizing time and experience. Suffused with allusions to his Jewish American identity and often taking the form of prayer, the poetry approaches the sacred via its own, idiosyncratic routes.

The poet Dana Gioia writes: “The expansive measure of the Hebrew prophets, which has proved irresistible to so many American poets, such as Walt Whitman and Robinson Jeffers, held no appeal for Menashe. He sought the vision underneath the reverberant rhetoric. He purified his poetic material into a private ritual language, simultaneously sacred and secular, perfected for his own purposes.”

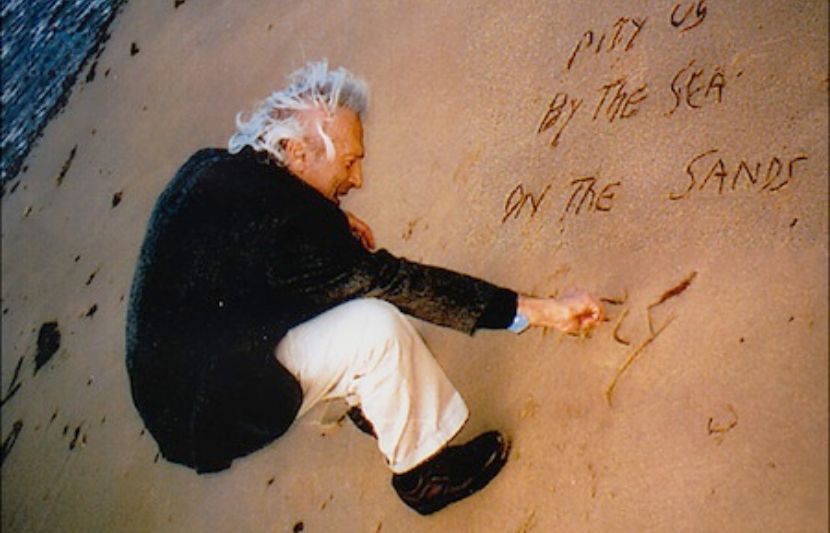

In this photograph by Martin Duffy, Menashe writes one of his poems on the beach: “Pity us / by the sea / on the sands / so briefly”

A religious echo is everywhere in Menashe. The English poet Stephen Spender compared his voice to “some kind of biblical instrument—tabor or jubal,” and scholar Stephanie Burt identified the poems as “ways for the solitary soul to communicate with, or aspire to, the sublime, the world beyond merely human communication, ways to speak with and to—though never for—the aniconic God.”

A World War II veteran who experienced the horror of ground combat, Menashe alluded to the link between faith and survivorship in a New York Times profile: “For the first few years after the war, each day was the last day. And then it changed. Each day was the only day.”

The best companion to Menashe’s work, one finds, is typically Menashe himself. A matchless reader of his own poems, he was also featured in a memorable 2009 episode of WNYC’s Know Your Neighbor series. “The struggle is against too many words!” he declares from the couch in his cozy, cluttered Greenwich Village apartment.

Watch: “Samuel, the Concise Poet” on YouTube

On the occasion of his centenary, what can we say of Menashe’s place in the American literary tradition? Gioia puts it well:

In death as in life, he stands perpetually outside the conventional categories—a solitary but significant figure. He must be read and savored on his own terms, an act that requires an independence of judgment and powers of sympathetic identification beyond the capacity of readers who feel most comfortable admiring what they have been taught to admire. . . . Reading his work requires attention and imagination, but the difficulties it presents are those of life, not literary analysis. Austere in style and classical in his self-detachment, he is nonetheless an accessible, vernacular writer who speaks to the common reader as strongly as to the intellectual. He will belong to such alert readers, fit though few.

In the years before his death, Menashe was a fixture at the LOA offices in New York and a frequent correspondent with our staff. A colleague recalls, “In his final months he often called me up and, during one of his illnesses, he asked me to take down a poem he had written in his head. A constant reviser, he believed this new work was ready for publication but was worried it would be lost before he could send it off. When he subsequently recovered, however, he tinkered with it some more and then submitted it to Poetry, which included it in the November 2010 issue.”

Below is the original version:

Who

Who can revive a relic

Liquify dry blood

Touch a corpse to the quick

Convert a monster to love

Who made man from mud