Photo illustration of Elmore Leonard depicting his signature glasses and cap

There are few experiences in American literature more thrilling than a sequence of Elmore Leonard dialogue. With an ear tuned to the unpretentious poetry and crackling rhythms of everyday speech, Leonard distilled a distinct prose style that combined the cinematic panache of genre fiction with incandescent language and unforgettable characters. From his early novels that pushed the frontiers of the Western to his later contemporary crime classics like Get Shorty, Rum Punch, and Out of Sight, he infused the base materials of page-turning potboilers with raucous humor, penetrating observation, and surprising moral insight.

In his new biography, Cooler Than Cool: The Life and Work of Elmore Leonard (Mariner Books, 2025), writer C. M. Kushins investigates the long arc of this matchless author’s multi-decade career, spanning five a.m. drafting sessions before clocking in at his advertising agency day job, forays into the vagaries of Hollywood filmmaking, and heartfelt reckoning with his spiritual beliefs. Below, Kushins discusses Leonard’s key influences and artistic aspirations, his lifelong engagement with his Catholic faith, and the complex considerations of craft and commercialism that informed his claim (amply realized) that he “wrote to be read.”

LOA: Elmore Leonard combined a superlative ear for dialogue with vernacular and propulsive prose (“If it sounds like writing,” he once said, “I leave it out”). What are the hallmarks of Leonard’s style?

C. M. Kushins: Leonard’s style was marked by incredible, realistic dialogue; it was something he had an instinctive talent for, but also honed over time. If you go back to his childhood, he would “tell” the plots of recent movies to his neighborhood friends, and then, in fifth grade, took his first stab at writing with a short play based on All Quiet on the Western Front.

I think he knew early on that his ear for dialogue was among his strongest storytelling abilities and he worked to craft a unique sound that emphasized it. Following his successful transition into the “contemporary crime” genre in the late 1960s, he admitted that he’d had trepidation about writing stories within a modern setting, as so many other successful authors already did it so well. His move from the Western into the contemporary world wasn’t as easy as many readers would assume.

Famously, he spent the first decade of his career getting up at five in the morning and writing at least one page of fiction before he’d even allow himself to have a cup of coffee.

A strong combination of working as a screenwriter during the early 1970s—as well as his famed discovery of George V. Higgins’ crime classic, The Friends of Eddie Coyle—helped shape Leonard’s signature sound. Much has been said about how Leonard’s admiration for Higgins is best seen by Leonard’s economic use of exposition and plot-driving dialogue, but I think that Higgins’ portrayal of his native Boston was a much more important revelation to Leonard. If you read Eddie Coyle, you can see how the city itself is a character in the larger tragedy of the story. Leonard immediately began using his own locales—Detroit and Florida among them—soon after. According to Leonard, Higgins also taught him the crucial lesson to start a story in the middle of the action, throwing the reader into the scene already taking place.

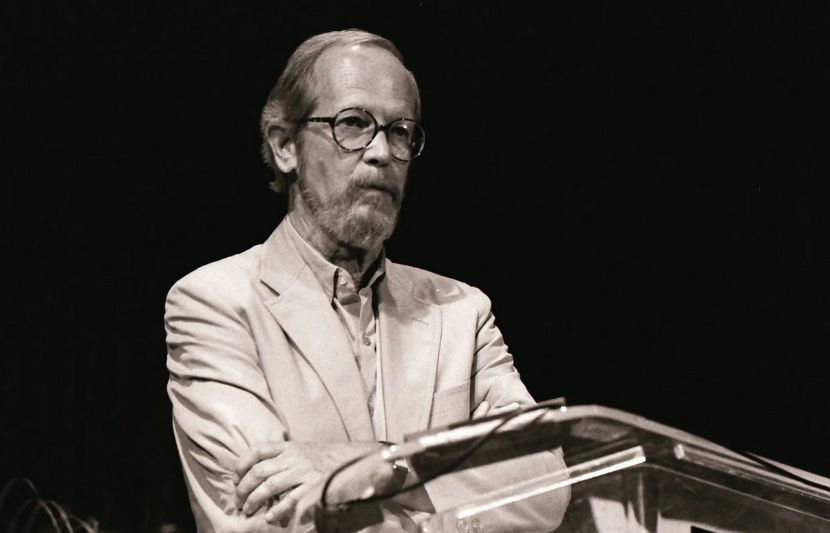

Elmore Leonard in 1990 (Marc Hauser Photography Ltd / Getty Images)

Among Leonard’s unique hallmarks—incredible dialogue aside—I would say that the balance of characterization between law enforcement, criminals, and “regular” everyday citizens (Leonard’s “decent man in trouble,” as The New York Times once dubbed them) is a key to deciphering his humorous take on human morality. That and the fact that his women are usually smarter than his men.

LOA: Leonard at one point constituted, in your words, “a one-man writing factory,” producing fiction, ad copy, and screenplays all at the same time. Can you discuss his tenacious work ethic and how he balanced his art with making a living?

CMK: Leonard was unique as a popular author in the sense that his philosophy and approach to storytelling was both uncompromising and pragmatic. If you go back to his father, Elmore Leonard, Sr., you see that the elder Leonard had youthful aspirations to become a fine commercial artist (Leonard’s son, Christopher, has one of his grandfather’s New Orleans seascapes hanging in his home) but had to set those ambitions aside when he was forced to join the workforce in his teens.

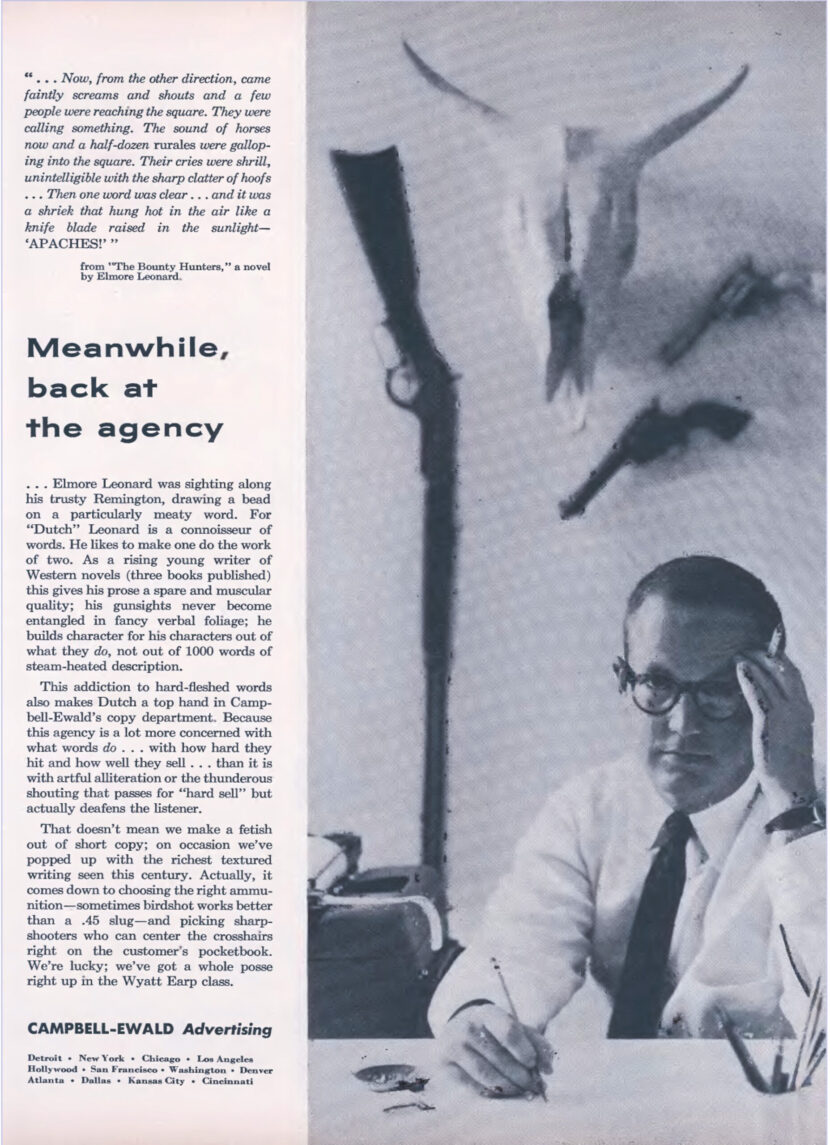

Decades later, in his twenties, Elmore Leonard nearly had to make the same decision when his father died rather young and Leonard attempted to purchase his New Mexico car dealership, apparently forsaking his own desire for a career in writing. It didn’t work out, but Leonard continued to work a full-time job in advertising at Campbell-Ewald while supporting a young wife, and soon, a growing family—all while writing Western fiction in the early mornings.

1956 Campbell-Ewald New Yorker ad featuring a young Elmore Leonard (Fair Use)

I think he knew early on that if he wanted to pursue a career in any creative trajectory, he’d need to do two things: have a stable “day job” that would support his family and stake his writing, and select a surefire genre that would allow him to keep selling fiction while getting better at writing it. Funnily enough, that practice didn’t really stop until the mid-1990s!

If you think about it, even when Leonard retired from advertising, he viewed his screenwriting work as just that—work—replacing the stability that copywriting had once provided while still allowing him to hone his prose.

Famously, he spent the first decade of his career getting up at five in the morning and writing at least one page of fiction before he’d even allow himself to have a cup of coffee. After helping his wife, Beverly, with the kids, he attended an abbreviated Catholic Mass on the way to Campbell-Ewald, then worked at the office until at least five in the afternoon. He kept this up with incredible discipline, even after his stories and novels began to sell and two films had been adapted for the screen. He took the advice of his first agent, the tenacious and brilliant Marguerite Harper, to heart and didn’t give up his advertising work until he knew he could survive first as a freelancer, then as a full-time author. Leonard’s story is really one of a lifelong, hard-won fight for creative independence.

LOA: Leonard developed his authorial skill in the Western genre, having deliberately chosen it for its commercial prospects. But his work was far from formulaic: he was an early practitioner of the “Revisionist Western” emerging in the 1950s and ’60s, and he incorporated Western elements into his later novels (Terrence Rafferty, editor of LOA’s Elmore Leonard: Westerns, claims, “In a sense, Elmore Leonard never really stopped writing Westerns”). How did Leonard’s relationship to the Western evolve throughout his career?

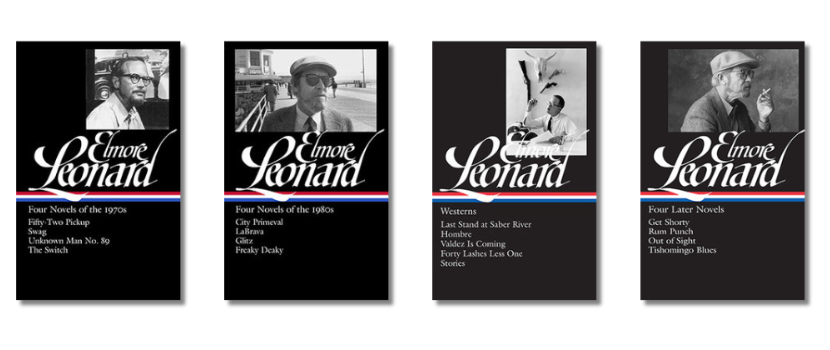

CMK: Without shamelessly praising the Library of America for its efforts, I have to say I loved all of the LOA Elmore Leonard volumes. Gregg Sutter and Terrence Rafferty did wonderful jobs editing those, and I strongly agreed with their selections.

Elmore Leonard in the LOA series: Four Novels of the 1970s, Four Novels of the 1980s, Westerns, and Four Later Novels

That being said, within Rafferty’s Western volume, I loved that he emphasized the progressive nature of Leonard’s earlier work. I wouldn’t say that it’s an aspect that most readers miss, only that most mainstream readers tend to gravitate toward Leonard’s contemporary crime fiction while shying away from the Western stuff, never realizing just how modern that work feels.

In fact, I think that Leonard’s own personal life and beliefs fueled much of his Western work in ways not necessarily present in his later crime writing. For example, Leonard’s Catholic beliefs and sense of the cultural zeitgeist (the civil rights movement and Vatican II, for example) show in the moral and ethical decisions that face his characters in even the earliest Western stories.

While he never eliminated those themes from his work, they are very evident in the short stories and Western novels—much in the way that Graham Greene wasn’t a Catholic writer, but was a writer who happened to be Catholic, and so his protagonists seemed to follow those same internal senses of guilt and justice.

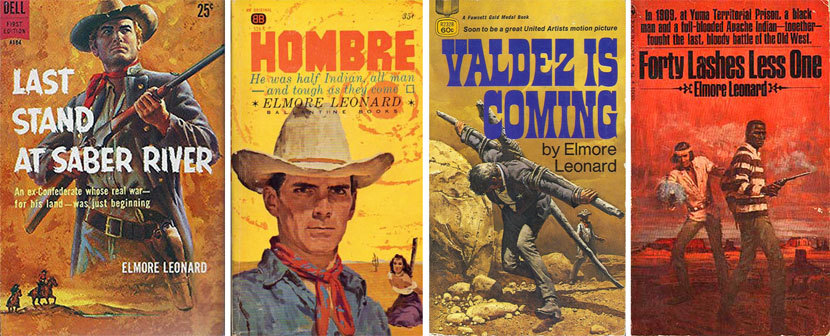

To me, Hombre is one of the best books ever written about racism and bias in any form, Valdez Is Coming is one of the coolest re-imaginings of the Christ mythology in modern fiction, and Forty Lashes Less One holds up staggeringly well as an early commentary on what became the privatized prison system. Not that Leonard had those aims in mind, however; he just claimed he enjoyed Western movies and told the stories he wanted to tell.

First editions (all paperback originals) of Last Stand at Saber River (1959), Hombre (1961), Valdez Is Coming (1970), and Forty Lashes Less One (1972)

LOA: Among Leonard’s key influences were giants like Hemingway, Faulkner, and Steinbeck, as well as less-known figures such as Richard Bissell and the aforementioned George V. Higgins. What did Leonard learn from these writers and how did he see himself in relationship to the American literary canon or his author peers?

CMK: There’s a great lesson in there, that even before he ever truly set pen to paper, Leonard began his career as an active reader—devouring almost anything that he could, first as a kid and later while serving in the Navy during World War II. As child, his mother subscribed to the Book of the Month Club and at night his older sister would read stories to him before bed. In the service, Leonard was privy to the same bundles of paperbacks sent to those stationed abroad—classics and dime-store novels alike. During those years, Leonard shaped his own percept of what “good and bad” writing was, coming to the conclusion that most writers “used too many words” and—as he famously recalled from Steinbeck’s Sweet Thursday—unnecessary, flowery exposition that Steinbeck had deemed “hooptedoodle.”

By the time Leonard graduated from college, he was taking his writing seriously and placed much of his self-education on studying Ernest Hemingway—his first real literary hero—and in particular For Whom the Bell Tolls, which Leonard regarded as a Western tale in literary guise. What Hemingway lacked, however, was the sense of humor that Leonard himself found in real life, but he soon discovered that in the writing of Richard Bissell—although he would also study John D. McDonald and some major contemporaries who graced the “slicks” like Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post.

Many years later, Leonard was established enough as a best-selling author that his time to read fiction for fun had significantly dwindled. He made it a habit never to read fiction while working on a book, instead poring over the volumes of necessary non-fiction and research provided by Gregg Sutter for the next project.

However, Leonard kept up lively correspondences with a number of his contemporaries—many of whom readers may be surprised to learn he knew. For example, he had fan letters from authors as diverse as Martin Amis, Raymond Carver, and Clive Cussler, and kept up correspondences with Margaret Atwood and Jim Harrison. I think in his later years, Leonard read all of those authors as a sort of mutual appreciation society—although he was still often labeled a “genre writer.”

Leonard in 1989 (CCA SA 3.0)

LOA: Leonard was raised Catholic, and though he stopped taking the sacrament later in life, he still reported that “it’s important to me to go through this little drill about what my purpose is before I get out of bed every morning.” Can you speak about Leonard’s relationship to religion and how it filtered into his fiction?

CMK: The subject of Leonard’s religious and spiritual beliefs interested me, too—especially since, as a child, I thought it was cool that both he and I went to Catholic school and were primarily taught by nuns. Leonard’s children told me that, when he was younger, his own Catholic beliefs were stronger than even his parents’ had been; up until the late 1960s, Leonard even served as a eucharistic minister and catechism teacher for his local parish.

Around that time, however, he also left Campbell-Ewald and began his first attempt as a freelance copywriter, temporarily putting his fiction writing on the back burner. One of the most lucrative ongoing gigs he had was writing short screenplays for industrial and education films, directed by an old friend. Leonard’s first screenplay—a recruitment film for the Franciscan Order—inadvertently initiated a lifelong friendship with the short documentary’s subject, a recently ordained missionary priest named Juvenal Carlson. For decades, the two would keep up a lively correspondence, no matter where in the world Carlson ended up on assignment, and Leonard would always pose his own spiritual questions to him, even when Leonard himself all but left the church in the early 1970s. When Leonard conquered his alcoholism in late 1970s, he managed to find much of the structure and daily affirmation that the church had once given him in his Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

I think Leonard reached a point in his life when the solace provided by organized religion and AA were no longer needed, and he was able to step away from both. But it was a personal thing to him. He continued to fund numerous Catholic charities and other philanthropic organizations that he didn’t necessarily take part in, yet continued to respect and praise. And he also continued to fuel his fiction with cool priests (albeit, fake ones), nuns, and strong protagonists that stuck to internal moral codes that seemed to demonstrate, at times, his own sense of higher justice.

LOA: “I’ve always seen my books as movies,” Leonard said, and fittingly his work has produced numerous film adaptations, from Western genre flops to ’90s neo-noir hits like Get Shorty, Out of Sight, and Jackie Brown. What about his fiction invites the cinematic treatment? And what are your favorite movie versions of books by Leonard?

Film adaptations of Leonard: Out of Sight (1998), Get Shorty (1995), Jackie Brown (1997), and 3:10 to Yuma (2007)

CMK: Leonard had no pretense in admitting that, even during his earliest years as a professional writer, selling his stories for Hollywood adaptations was a key goal. Not only had both of his agents (Marguerite Harper until her death, then Hollywood power broker H. N. Swanson) encouraged him to switch to contemporary settings and styles, but also to write sellable work that would keep readers and audiences wanting more.

Although Leonard never compromised his writing style, he always claimed that he “wrote to be read” and he, himself, loved movies—if they were good. Nothing seemed to frustrate him more than if one of his screenplays or novels was turned into a bad film; he didn’t mind a director making changes if it improved the story for the screen. Look how Get Shorty, Out of Sight, and Jackie Brown are all dynamic adaptations that Leonard adored, yet those respective filmmakers made necessary changes to properly adapt the stories to new mediums. That didn’t seem to bother Leonard if the film worked; as he said, the book was his.

He often admitted that when a filmmaker or producer would read his work, they would see his style beckoned adaptation: a set of chronological scenes, driven by great dialogue that furthered both the characterization and the story. Although Leonard later said that, despite his playful jabs, Hollywood had “been good” to him, and I believe he really felt that way. You could see the joy on his face when he visited the set of one of his adaptations and the cast and crew were genuinely excited to see him there. But I also think that he was somewhat relieved when, blissfully in his seventies, he could wake up in the morning and just write—allowing other, younger screenwriters to adapt his work while he could keep his focus on fiction.

My favorite adaptation will always be Get Shorty. As a child, it was my first encounter with anything written by Leonard, and I was fortunate enough to have read the book right before the film came out. I absolutely loved both and became a devoted Leonard junkie for the rest of my life. I will say, though, that both Out of Sight and Jackie Brown are close contenders, since they truly bring Elmore’s sound to life on the screen. I have to give credit, however, to Paul Schrader, who made a really faithful and cool adaptation of Touch in 1997. For decades, Leonard had been told that the story was, more or less, unfilmable, and I think Schrader proved that wrong by sticking to the book.

LOA: With dozens of books to choose from, it can be hard for readers to know where to start with Leonard. What recommendations would you give to those eager to begin exploring his oeuvre?

CMK: Well, normally this would be a tough one, but Library of America made it easy! If a reader is new to Leonard’s work, I highly recommend the four volumes that LOA put out; they’re excellent cross sections of Leonard’s career and, if you like a specific volume, you can easily go on to read his other works from that era. But if you can get hooked by Westerns, try and go in chronological order.

However, for real newbies, I always recommend the short stories—especially since I love the collection Fire In the Hole (originally When the Women Come Out to Dance). After that, I revere Leonard’s Carl Webster Saga—including Cuba Libre, The Hot Kid, Comfort to the Enemy, Up In Honey’s Room, and an incredible short story titled “Tenkiller.”

After that, I’ll bet you’ll want to read everything he ever wrote.

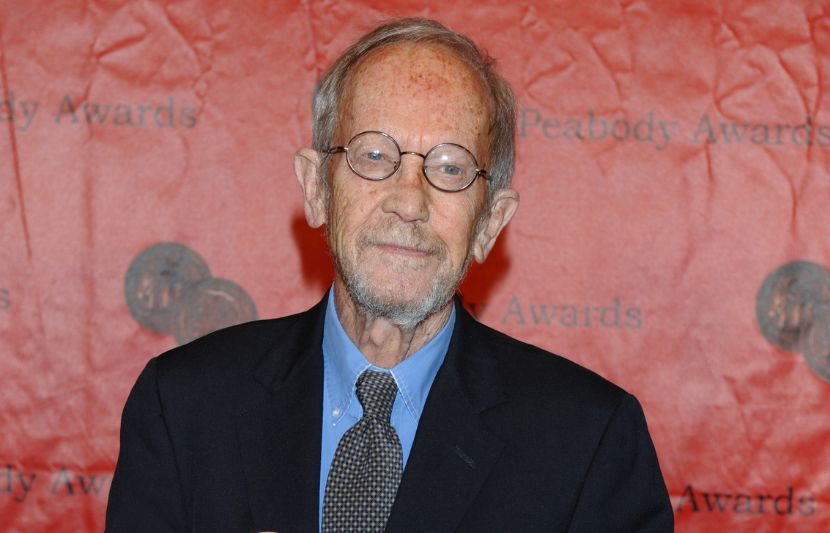

Leonard at the 70th Annual Peabody Awards Luncheon in 2011 (CC BY 2.0)

C. M. Kushins is the author of Cooler Than Cool: The Life and Work of Elmore Leonard, Nothing’s Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon, and Beast: John Bonham and the Rise of Led Zeppelin. He has been a freelance journalist for over fifteen years and his work has appeared in High Times and The Daily Beast, among others.