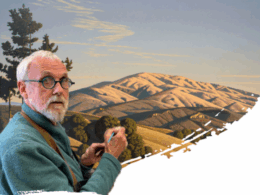

We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine (Liveright, 2025) by Alissa Wilkinson

When Joan Didion was a child, living with her family on army bases, she saw a 1943 Western starring John Wayne called War of the Wildcats and was transformed forever. First as a celebrated novelist and essayist, then a screenwriter, and later a trenchant political observer and electrifying memoirist, she tracked Hollywood’s evolving influence on American life and culture, seeing firsthand how the world of entertainment shaped the nation’s aspirations and ideology.

In her recent book We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine (Liveright, 2025), New York Times film critic Alissa Wilkinson reappraises one of our most iconic writers, chronicling how Didion realized that the movies she herself wrote, reviewed, and revered had wrested control of reality. Below, Wilkinson speaks with Library of America about Didion’s lifelong engagement with the power of cinema and the strange afterlife of her most-quoted phrase.

LOA: You write about Joan Didion’s love of film as a child, how it presented her with myths of America that set the template for topics she’d wrestle with for her entire career. Where did Didion’s interest in movies begin and where did it lead her?

AW: An interesting connection between Didion and Hollywood is that she was born in 1934, the year that the Hays Code, officially the Motion Picture Production Code, started being enforced. She grew up in an era when Hollywood saw itself as the guardian of American moral purity, and because of that, the movies she would have seen were part of what we think of today as the Golden Age of Hollywood: these big stories, a lot of them adapted from plays, fairly squeaky clean, many of them Westerns (because you could get away with stuff in a Western that you couldn’t in a household drama).

She was a lonely child, raised in a politically conservative environment. Her father was in the Army Air Corps, and until she was eight they were traveling all the time, living on different bases. Movies were her solace as a shy kid. She writes about watching a John Wayne movie at Peterson Air Force Base, and he becomes the biggest figure looming in her love of Hollywood: this handsome, larger-than-life man who represents adventure and courage. He also has something to do with her pioneer ancestors, a mythology that’s really important to her as a Californian.

John Wayne and Martha Scott in War of the Wildcats (1943), which Didion recalled watching as a child (Public Domain)

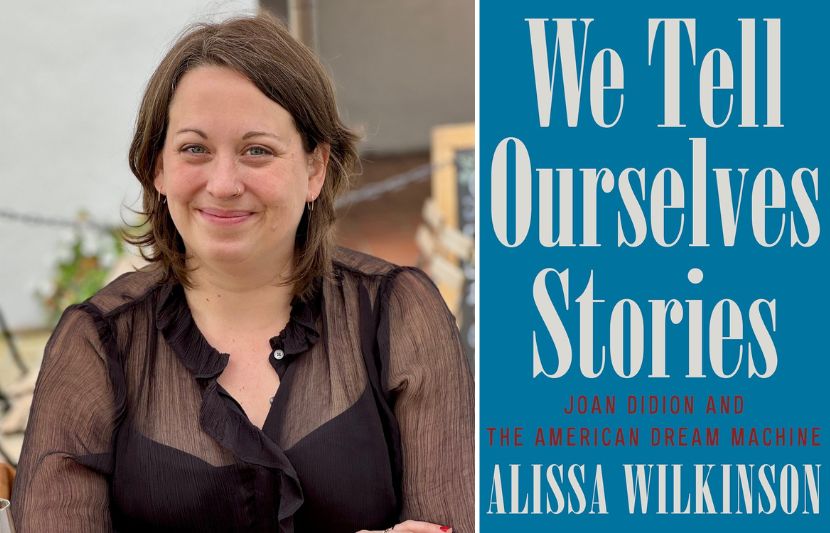

She moves to New York City after college and eventually becomes a film critic at Vogue (where she briefly shared a column with Pauline Kael). Then Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, moved to Los Angeles to see if they could hack it in the film business. Dunne’s brother was a TV producer, and Didion and Dunne were very good networkers, but they remained nonchalant about screenwriting as an art form. It was more of a job for them, a way to make a living, and that’s why a lot of the films they wrote are quite commercial.

When they returned to New York in the 1980s, Didion became a political writer, having seen the rise of Richard Nixon and then Ronald Reagan in the intervening years. Reagan in particular was a Hollywood figure, someone who viewed his governorship and then his presidency as akin to being an actor managed by a studio on the set of a film. Didion wrote a very mean, very great piece called “Pretty Nancy,” about spending the day with Nancy Reagan at the governor’s mansion in California. Her opinion was that this was a nonsense person doing nonsense things.

I don’t think Didion ever lost her love of Hollywood, but she was disturbed by it becoming the political culture as well as the entertainment culture of the country.

LOA: Can you explain why Didion found this convergence between Hollywood thinking and American politics so singularly troubling?

AW: Didion worked in Hollywood for a couple of decades. She was on sets, her movies were produced, she went to premieres, she went to Cannes. She knew how studio heads changed the message of a film or the characters based on focus groups. They weren’t committed to a particular story but rather to whatever was going to make a good haul at the box office.

Posters of films written by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne: A Star Is Born (1976), The Panic in Needle Park (1971), and True Confessions 1981)

There’s an essay in the book Political Fictions called “Insider Baseball” where Didion is following the Dukakis campaign and incorporating what she’s seen on Jesse Jackson’s and others’ campaigns. On the surface she’s covering the campaign like any political reporter, but in actuality she’s watching the political reporters more than the candidates, watching the cameras filming the candidates, listening to the handlers—doing the typical Didion thing of taking two steps back and paying attention not to the thing that’s being said but the way what’s being said has been crafted.

Didion has a very clear picture of how the sentimental storytelling Americans have been doing for decades has leaked so far into the way we think that we don’t have another way of filtering reality anymore.

To her mind, people have started imagining their leaders through the lens of movies, and the candidates now have to be packaged that way. She sees this happening over and over, and she is very equal opportunity about it. She doesn’t think George W. Bush knows what he’s talking about, she doesn’t like Bill Clinton. They’re all being packaged for the camera in a way that’s designed to speak directly to the sliver of the American public that the pollsters have decided are the ones who matter. That is Hollywood logic.

On top of it, she sees a sentimentality that comes straight from the Hollywood playbook, a promise that reality will work the way a Hollywood story does. Peril comes, but then a leader arrives and saves us. That makes space for demagoguery in a big way.

LOA: Several times you mention Didion encountering “cracks in the narrative,” where her established thinking suddenly crumbles. Can you talk about Didion’s own susceptibility to political fictions and pernicious nostalgia?

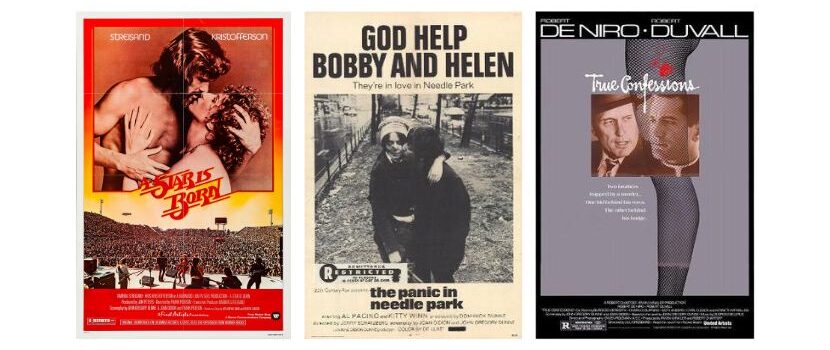

AW: Didion’s 2003 book Where I Was From is a reexamination of what she calls the “official mythology” of California—stories she was handed down from her ancestors about their perilous journeys across the West, their courage, how they left everything behind and struck out on their own. The standard American mythology.

Her mother was always proud that the family never took money from the government, and it wasn’t until Didion was an adult that she realized that was a load of hogwash. There are whole towns in California that only exist because of postwar federal funding. Tons of people only went to universities because of the GI Bill. Didion’s own family was in the military! Didion just saw it suddenly for what it was: a fiction that Americans told themselves to fit the larger story of independent, courageous, go-it-alone people.

She reads that idea into a bunch of news stories set in California, but in a lot of cases you can substitute in America more broadly, because the American story is not all that different. This, of course, is very tied up with Hollywood, with the Western being probably the most American of genres you can imagine.

Joan Didion with her family on an army base in 1943 (joandidion.org), 1850 image of the California Gold Rush, and the California State Fair in 1950 (Sacramento Public Library)

There’s an essay that was printed in book form called Fixed Ideas: America after 9/11. As background, Political Fictions was supposed to be published on September 11, 2001, but got delayed a week due to the attacks. A week after 9/11, Didion flew to California to start a book tour. She writes about going west and people seeming very clear-eyed about the causes—or potential causes—of what had just happened in New York.

Then she comes back to New York, where she’s living, and she says it’s as if she’s entered a parallel dimension, with flags everywhere and nobody allowed to even imply that there might be any history coming to bear in the 9/11 attacks. Instead, these are merely acts of aggression for no reason. To her that is a fixed idea: an idea that’s not permitted to be changed or talked about, and that comes from deep inside our psyches. Didion in her sixties and seventies has a very clear picture of how the sentimental storytelling Americans have been doing for decades has leaked so far into the way we think that we don’t have another way of filtering reality anymore.

LOA: She applies the same ideas to her personal life in The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, where she dismantles her own personal myths and tries to make sense of the incomprehensible. And her technique for doing that involves the metaphor of film.

AW: All the way back to her essay about leaving New York City, “Goodbye to All That” in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, she uses the language of film, of editing and montage. This is long before she worked in Hollywood.

Later, in The Year of Magical Thinking, she talks about running the tape back, wanting to bring the reader into the editing room with her so they can understand the story the way she does. The book has a cyclical structure, where she’s revisiting the same events over and over, trying to make sense of them, and she sees that as literally rewinding a tape of herself and rewatching it.

For me, this felt very moving and real, because when you experience something senseless or you’re experiencing grief, it’s very hard to shake the idea that you know how this movie goes. We say, “It’s like a movie.” When 9/11 happened, that’s how people described the experience repeatedly in papers across the country: “It’s like watching a movie. It’s like being in a movie. It feels just like a movie.” That should tell us something about how we’re processing reality collectively.

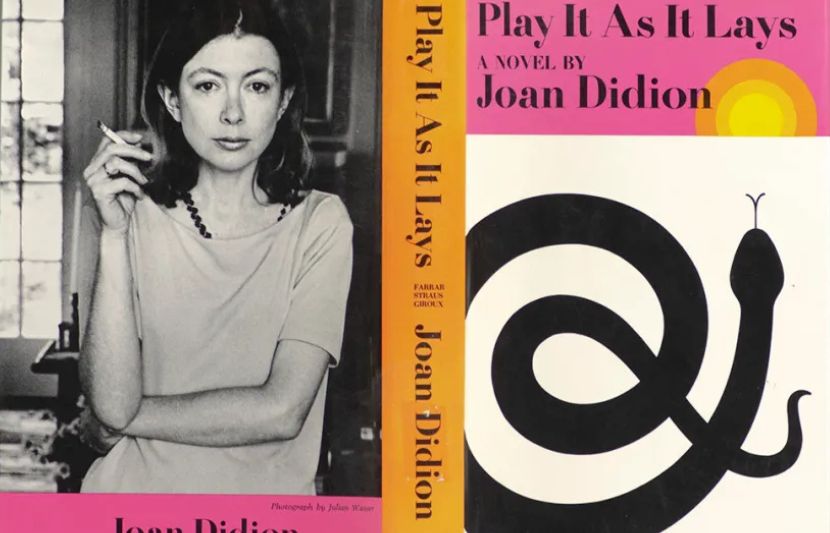

First-edition jacket of Play It as It Lays featuring iconic photograph of Joan Didion by Julian Wasser (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970)

LOA: The title of your book comes from one of Didion’s best-known phrases, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Could you unpack that line for us? How has it been misinterpreted, and what did Didion mean by it?

AW: The phrase comes from the first line of her essay “The White Album,” the first essay in her book The White Album. I have a Google Alert set for it and I can tell you that every single day someone quotes that phrase on the Internet, and they’re always trying to encourage people to submit to their literary magazine or talking about the importance of telling your own story. But that line actually describes a world in which the headlines are chaotic and the stories don’t make sense. Didion is saying that our impulse is to create a story so we can make sense of reality. That way we can keep on living, because if we didn’t have a story to lean on, we’d go insane.

Many people have taken the phrase out of context and used it as an inspirational slogan. But really, it’s the guiding principle for reading Didion’s work. She’s trying to see the story underneath the thing that’s happening. A politician gives a speech, but what’s more interesting is the story that we tell ourselves that enables us to listen to and agree with that speech.

It occurred to me that the first half of the line, “We tell ourselves stories,” had multiple shades of meaning for the kind of work I do, because it’s also a description of Hollywood: America telling itself stories, trying to repeatedly roll back the tape and reread our history or our daily lives in ways that allow us to make sense of them.

In recent years, I’ve thought a lot about the idea of “main character energy” or “doing it for the plot.” This pops up on social media among young people as if it’s a new idea. I don’t know anything that’s more illustrative of the need to believe we’re living in a story in order to feel like we’re really living. Didion nailed it with that line. Clearly it resonates, just not always for the reasons people think.

LOA: Didion is the rare writer who inspires ardent fandom and could qualify as a celebrity. Could you talk about Didion as a star, how she signifies not just a historical person or a writer, but almost a lifestyle or an idea: a person you might wish to be?

AW: This started for her in the 1970s. She had published Slouching Toward Bethlehem and Play It as It Lays and The White Album. Women were flocking to her as if she had the secret to the universe—that’s how she puts it. She doesn’t come across as shy in her prose, but she was a very shy person, so this newfound attention was both gratifying and somewhat unnerving and befuddling.

If anyone’s ever seen a picture of Joan Didion, it’s probably the famous Julian Wasser photo that was printed on the back of Play It as It Lays, with her in a long dress, smoking. If you read that novel and saw that woman, you might think, “That’s how I want to be.”

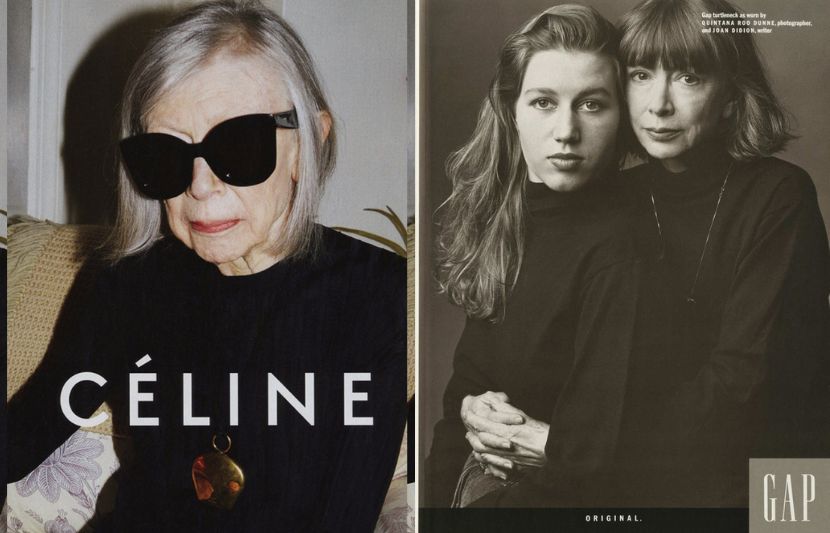

Didion is an interesting figure because she understood the pitfalls of celebrity, and while she didn’t court it exactly, she also didn’t turn it away. She did Gap ads with her daughter and later did a Céline ad in her eighties. The image of her was cool and reserved and very chic, and also just insanely talented—one of the greatest writers of her generation. That is so appealing if you’re a certain kind of writer and reader, and especially if you’re a certain kind of woman.

Joan Didion in 2015 Céline campaign and Didion and daughter Quintana Roo Dunne in 1989 Gap ad photographed by Annie Leibovitz

Didion is a blank enough slate that you can project anything on to her. She represents a lifestyle that’s very appealing and also completely unattainable for most writers. But she also has this air about her. If you did a word cloud of adjectives that have been printed to describe her, it would include “cool,” “sophisticated,” “reserved,” “sharp,” and so on.

She’s a brand and brands appeal. She gets at this in a 2000 essay for The New Yorker, ostensibly on Martha Stewart but really about Didion creating a personal brand, having fans who love her for her work, but who also really love her for her image and what she represents to them, and the kind of parasocial, aspirational relationship they can have with her.

LOA: Does the power of Didion’s persona run the risk of obscuring her purely literary accomplishments? What do you ultimately return to when you consider her legacy?

AW: I recently recorded an audio version of my book, and something I realized was that it’s wildly hard to read Joan Didion aloud. This struck me as very interesting, because while I love her writing, it runs against my one rule when I teach writing, which is you should never write anything you wouldn’t say aloud.

Maybe Didion would talk like that—I don’t know. But I think that her language is a little obfuscating, and that’s on purpose. Like many writers who write in almost a monotone at times, she wants you to lean in and pay attention. It’s not that she’s especially demanding or difficult to read, she just trusts the reader and insists they get involved.

That’s one reason I keep coming back to her language. For her, the rhythm of the words was what she had first, and the words themselves came afterwards. I intuitively understand that as a writer. For her, the ways things sound and move and feel is very important. And that was my initial attraction to her writing—the feeling of being inside a brain rather than receiving beamed-out messages from a brain.

All the pieces of her personality and her thought and her evolution are in tension with one another, and at the end of the day, what I find most instructive is that she never settled on one way of thinking. Her late books are all about reevaluating the way she thinks. That is so gutsy for a writer to do, especially an older writer, especially an eminent writer. I wish more writers would do that. We tend to get more set in our ways the older we get, but she was still surprising herself right up until she stopped writing.

Alissa Wilkinson is a film critic at The New York Times and was formerly a senior correspondent and critic at Vox. She is the author of We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and The American Dream Machine (2025) and Salty: Lessons on Eating, Drinking, and Living from Revolutionary Women (2022).