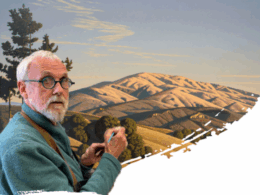

Artist David Ligare and his painting Mountain (2013)

In his poem “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction,” Wallace Stevens writes:

Two things of opposite natures seem to depend

On one another, as a man depends

on a woman, day on night, the imaginedOn the real.

In literature as in the visual arts, ideas about representation and abstraction, reality and imagination, are not irreconcilable but mutually illuminating. John Steinbeck, a skilled practitioner of social realism, still managed to transmute his closely researched, unabashedly activist fiction into novels that have only grown in symbolic and political power.

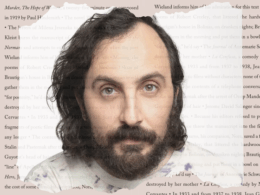

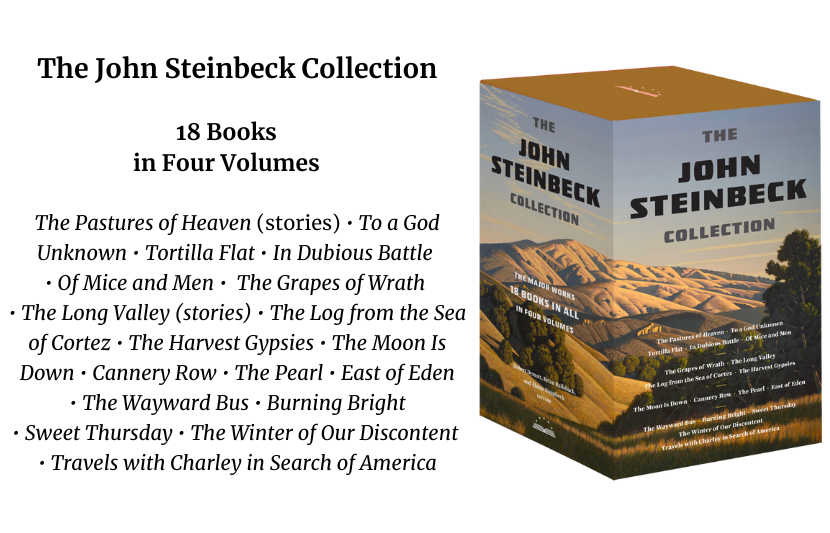

The art of painter David Ligare, whose work Mountain (2013) will adorn the cover of Library of America’s four-volume boxed set of Steinbeck’s collected works (forthcoming, March 2026), has similarly sought the deep reservoirs of meaning and knowledge contained within meticulous and beautiful visions of the real. In this interview, the acclaimed postmodern, neo-classic artist discusses the impact of American literature on his life and work, the idea of pastoralism, and the intersection of art and life he finds in volunteering.

We thank Mark Melnick, graphic designer and longtime Library of America collaborator, for introducing us to Ligare’s art and choosing his work for the Steinbeck case.

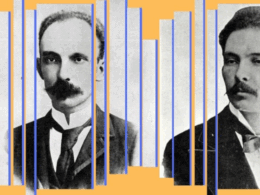

LOA: John Steinbeck and the poet Robinson Jeffers were important reasons for you moving to Monterey County, California. Why did these writers draw you to this place, and what has it been like living there?

David Ligare: I grew up in Manhattan Beach, a suburb of Los Angeles. I really wanted to live somewhere that was wild. When I finished college and my military service, I was inspired by Robinson Jeffers to move to Big Sur. Jeffers had described that landscape in mythological terms and that later influenced my painting. I had also read Steinbeck, whose belief system was just about opposite that of Jeffers. Jeffers described himself as an “inhumanist” and Steinbeck was certainly a true humanist.

Robinson Jeffers and John Steinbeck (Public Domain)

LOA: How has literature—Steinbeck’s novels and works by other authors—influenced your painting? What relationship do you see between the disciplines of visual art and writing?

DL: Both Steinbeck’s and Jeffers’ writings were inspired by biblical and classical literature, respectively. After doing an exhibition in New York in 1979 I decided to turn away from contemporary art because there were so many artists doing all styles and aspects of it, and to begin making paintings based on Greco-Roman narratives. It was a subject that I knew very little about, so I began reading and looking at images in books and museums. I thought that if Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning’s “action” was paint handling, my action was studying. While I believe that all manner of modern art is valid, I believe that it is now time to return to earlier methods of painting and thinking. As I have said and written for a long time, as a culture, we are in need of a renewed desire for knowledge. It is once again new territory for the artist.

Mountain (2013) by David Ligare

LOA: In an interview posted to your website, you speak about the need for representational art that is “not fixed to the present but is historically fluid and flexible.” Do you perceive a link between the literary or social realism practiced by Steinbeck and this approach to painting?

DL: One of the ancient authors I read was Ovid. In his Metamorphoses he related the story of an old couple, Baucis and Philemon, who take in two ragged homeless people who were actually the gods Jupiter and Mercury testing the people in their community. I made several paintings of this subject, one of which is in the Wadsworth Atheneum, but I also began working as a volunteer in homeless shelter in Salinas, California, the town where Steinbeck was born. It seems impossible to me now, but I worked there once a week for twenty-three years. My painting Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches was inspired by food that we served in the shelter dining room. I had discovered in my study that there was a kind of ancient tradition where a food gift was made to strangers that was called a xenia. It is an example of a subject that is ancient and modern both.

The idea is that an area that appears perfect under the surface contains stories that are sweet and sad and even tragic.

LOA:Your painting Mountain (2013) will grace the case of Library of America’s forthcoming boxed set edition of Steinbeck’s collected works. Can you tell us about this painting? What does it depict and how did you approach creating it?

DL: I did an exhibition at the Fresno Art Museum called “River/Mountain/Sea” about the three primary elements in Monterey County where I live. The river is the Salinas River that Steinbeck wrote about, the sea is our beautiful coastline, and the mountain is Mt. Toro, a prominent feature of our landscape, most particularly Corral de Tierra, a lovely valley where we’ve lived for thirty years. John Steinbeck wrote a book about this area called The Pastures of Heaven. The idea of the pastoral landscape was first written about by Theocritus and Virgil. I had made a particular study of “pastoralism,” as it is called. The idea is that an area that appears perfect (arkadia) under the surface contains stories that are sweet and sad and even tragic. Mt. Toro stands watch over the pastures of heaven.

The Pastures of Heaven by John Steinbeck (Brewer, Warren and Putnam, 1932)

LOA: Steinbeck remains one of our most revered and widely read novelists, close to a century after his literary debut. What do you think explains his longevity and continuing relevance?

DL: John Steinbeck was a humanist, although I’m not sure he would have called himself that. He deeply understood the human condition and presented it with a powerful empathy that continues to resonate with so many people today.

LOA: Are there works of Steinbeck’s you’d recommend to our readers? And, in the spirit of summer reading, what books—in any genre—have you been enjoying recently?

DL: For lighter summer reading The Pastures of Heaven is perfect. Of Mice and Men is also short but heavier. The Grapes of Wrath is the heaviest but, like other of his books, it is both biblical and modern. The book that I am currently reading is George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Scenes of Salinas Valley, California (Public Domain)

LOA: Can you share a little of what you’ve been working on lately? Do you have any upcoming shows or exhibits curious readers might check out?

DL: Humanism is very much on my mind these days, as I recently completed a large painting of the father of humanism, Petrarch, standing on the top of Mont Ventoux in the south of France. His ascent of the mountain in 1336 was considered by some historians to have been the “first Modern act” because it was done for purely secular reasons and because, as a writer and a philosopher, he had reached into the ancient past to create the future.

I did an exhibition in New York last year called “A Specific View.” This November I will be doing an exhibition at Winfield Gallery in Carmel, California, called “Spheres of Influence.”

David Ligare’s paintings are in numerous permanent collections of prominent institutions, including, among others, the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the de Young Museum, San Francisco; the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT; the Frye Art Museum, Seattle; the San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA; and the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.