This essay was originally published as an e-mail newsletter on July 19, 2025, commemorating the 175th anniversary of Margaret Fuller’s death in 1850. Sign up to get more articles on American literature and history delivered straight to your inbox.

1800s illustration of Margaret Fuller with Giovanni Ossoli and their child on the sinking ship Elizabeth (Public Domain)

In July 1850, the New-York Tribune’s first female foreign correspondent, Margaret Fuller, sailed from revolution-torn Italy to the United States a changed woman. Accompanying Fuller on the ship Elizabeth were her romantic partner Giovanni Ossoli, a minor nobleman and former soldier in Rome’s Civic Guard; their child, Angelo; and a draft of Fuller’s manuscript on the rise and fall of the Roman Republic, which she believed to be her greatest work—“something good which may survive my troubled existence,” as she wrote to her brother.

The young family and Fuller’s magnum opus would never reach their destination. In the early morning hours of July 19, an inexperienced first mate rammed the Elizabeth into a sandbar fewer than three hundred yards from New York’s Fire Island. As passengers and crew evacuated and swam for shore, where a crowd had gathered to watch the wreck and scavenge debris, Fuller, Ossoli, and Angelo stayed behind: Fuller could not swim. Angelo’s body ultimately washed onto the beach, but Fuller and Ossoli were never found. Also lost in the wreck was Fuller’s manuscript, prized by the writer as “what is most valuable to me if I live of any thing.”

Eerily enough, Fuller seemed to sense her return voyage to America would be ill-starred. In a letter to her friend Costanza Arconati Visconti dated April 6, 1850, she writes:

I am absurdly fearful about this voyage. Various little omens have combined to give me a dark feeling. Among others just now, we hear of the wreck of the ship Westmoreland , bearing [sculptor Hiram] Powers’s Eve. Perhaps we shall live to laugh at these, but in case of mishap, I should perish with my husband and child perhaps to be transferred to some happier state; and my dear mother, whom I so long to see, would soon follow, and embrace me more peaceably elsewhere.

Adding to the uncanny coincidences, another of Powers’s works was aboard the Elizabeth when it sank, this time a bust of South Carolina statesman John C. Calhoun.

As Brigitte Bailey, Noelle A. Baker, and Megan Marshall, the editors of Library of America’s edition of Fuller’s collected writings, discuss in an interview on our website, Fuller’s death at age forty set off a committed, if misguided, effort among her Transcendentalist peers to commemorate her achievement—albeit on terms they found palatable. Baker explains:

After her death, her friends Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Freeman Clarke, and William Henry Channing began assembling materials for a memoir and selected writings of Fuller, and in the process, they wreaked havoc on her papers. They excised and separated her journals. They effaced lines of text they considered radical or unwomanly. They regularized her writing with multicolored pens and pencils. They generated complete misrepresentations: in one example, a transcription of a journal fragment, in a hand other than Fuller’s, with accompanying commentary from the editors, is pasted onto an authentic journal fragment and then defaced again with inked-out lines and substituted words.

Thanks to the remarkable textual scholarship of these editors, the LOA edition of Fuller’s writings represents a reclamation of her authentic voice against the tides of time and censorship. But what of the lost Italian manuscript?

Rome under bombardment by French troops in 1849 and Roman soldiers of Giuseppe Garibaldi (Public Domain)

Though Fuller’s friends, including Henry David Thoreau, who had been sent by Ralph Waldo Emerson, traveled to Fire Island to “obtain on the wrecking ground all the intelligence &, if possible, any fragments of manuscript or other property,” only some letters and the journal Fuller had kept in Rome were recovered.

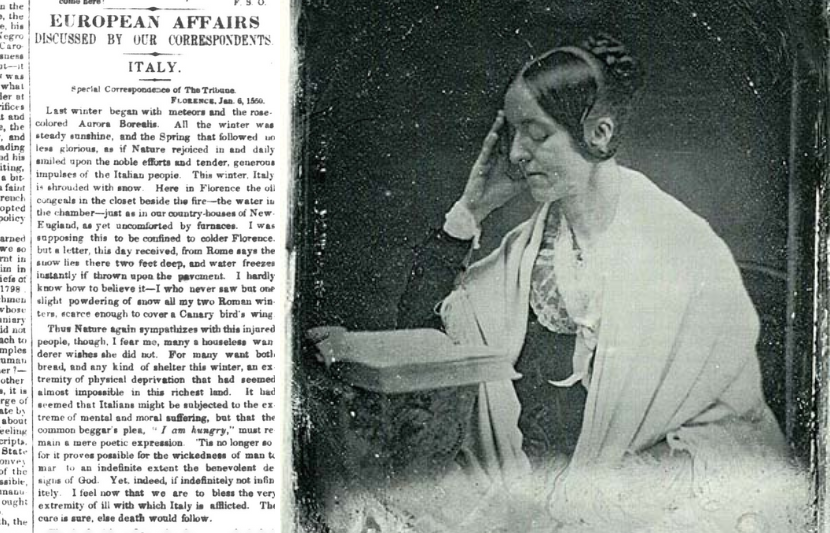

We can only speculate about the lost manuscript, but Fuller’s dispatches for the New-York Tribune provide a vivid window in her experience of the Risorgimento and the uncompromising politics she cultivated in its midst. In her final column for the paper in January 1850, she writes:

The next revolution, here and elsewhere, will be radical. . . . It will be an uncompromising revolution. England cannot reason nor ratify nor criticize it—France cannot betray it—Germany cannot bungle it—Italy cannot bubble it away—Russia cannot stamp it down nor hide it in Siberia. The New Era is no longer an embryo; it is born; it begins to walk—this very year sees its first giant steps, and can no longer mistake its features. . . . At this moment all the worst men are in power, and the best betrayed and exiled. All the falsities, the abuses of the old political forms, the old social compact, seem confirmed. Yet it is not so: the struggle that is now to begin will be fearful, but even from the first hours not doubtful. Bodies rotten and trembling cannot long contend with swelling life. Tongue and hand cannot be permanently employed to keep down hearts. Sons cannot be long employed in the conscious enslavement of their sires, fathers of their children.

Sounding a note of hope amid the violence and chaos of political strife, Fuller articulates the view that night is darkest before the dawn. Just as death and bowdlerization could not silence her true voice, so too does the quashing of rebellion leave an afterglow of ideals and aspirations, ready to be taken up by the next generation. One hundred seventy five years after she drowned with her family and her masterpiece, Fuller’s unvanquished message continues to ring out.

Scan of Fuller’s final dispatch for the New-York Tribune and daguerreotype of Fuller from 1846 (Public Domain)