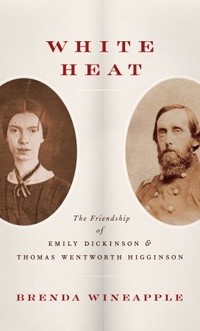

Brenda Wineapple wonders in White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson if Higginson’s extra-literary background as minister, ultra-abolitionist, feminist, and soldier made him the most incongruous correspondent for the hermit of Amherst—or the most inevitable.

Higginson (whose birthday is today) was a regular contributor to The Atlantic Monthly; his essays ranged across flowers, birds, women’s rights, physical fitness, and abolition. In the April 1862 issue his “Letter to a Young Contributor” described every editor’s ambition “to take the lead in bringing forth a new genius.”

Later that month Higginson received an unsigned six-line note that began “MR HIGGINSON, — Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” Enclosed with the note were four poems: “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers,” “The nearest Dream recedes unrealized,” “We play at Paste,” and “I’ll tell you how the Sun rose. ” Inside another smaller envelope was a card signed Emily Dickinson.

Higginson had never read poems like this before. He found them too strange to publish but he was eager to learn more about the author. He quickly responded with a few small criticisms and a host of questions—and began a correspondence that would last the next twenty-four years. During that time he received hundreds of poems (Dickinson otherwise shared her work only with her brother’s wife), yet he never published, nor suggested she publish, any during her lifetime. After her death he collaborated with Mabel Loomis Todd to edit and publish the controversial (and best-selling) first collection of Dickinson’s poetry—controversial because of their extensive editing of her distinctive punctuation and spelling.

We are indebted to Higginson for his rare account of a personal interview with the reclusive poet. After eight years of corresponding, they finally met in her parlor on August 16, 1870, as he recounted in The Atlantic Monthly twenty-one years later:

After a little delay, I heard an extremely faint and pattering footstep like that of a child, in the hall, and in glided, almost noiselessly, a plain, shy little person, the face without a single good feature, but with eyes, as she herself said, “like the sherry the guest leaves in the glass,” and with smooth bands of reddish chestnut hair. She had a quaint and nun-like look, as if she might be a German canoness of some religious order, whose prescribed garb was white piqué, with a blue net worsted shawl. She came toward me with two day-lilies, which she put in a childlike way into my hand, saying softly, under her breath, “These are my introduction,” and adding, also, under her breath, in childlike fashion, “Forgive me if I am frightened; I never see strangers, and hardly know what I say.”

But she quickly found her voice:

She went on talking constantly and saying, in the midst of narrative, things quaint and aphoristic. “Is it oblivion or absorption when things pass from our minds?” “Truth is such a rare thing, it is delightful to tell it” . . . “How do most people live without any thoughts?” . . . Or this crowning extravaganza: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

His 1891 recollection omitted two memorable lines he wrote to his wife shortly after the meeting:

I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching me, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her.