Library of America’s latest “Influences” guest post comes to us from Fernando A. Flores, whose new collection of short fiction, Valleyesque: Stories, is published this week by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

The fourteen stories in Valleyesque further establish Flores’s claim to the territory he has made his own over two previous books: a U.S.–Mexico border country rendered with equal parts satire and surrealism, where possums can run for public office, Frédéric Chopin grieves for the piano seized by customs officials, a used clothing warehouse contains a portal to a parallel dimension, and a young Lee Harvey Oswald pieces together a career as an aspiring musician.

Author Kali Fajardo-Anstine, herself an earlier “Influences” contributor, says of the book, “Reading Valleyesque feels like entering a new dimension, a southwestern twilight zone where slacker outcasts and political gangsters rub elbows with hallucinatory muralists. But the genius of Flores’ work is precisely that this is our world—a reality steeped in humor and chaos with an undercurrent of divine order.”

Below, Flores relates his discovery of a literary forebear who should be better known than he is.

By Fernando A. Flores

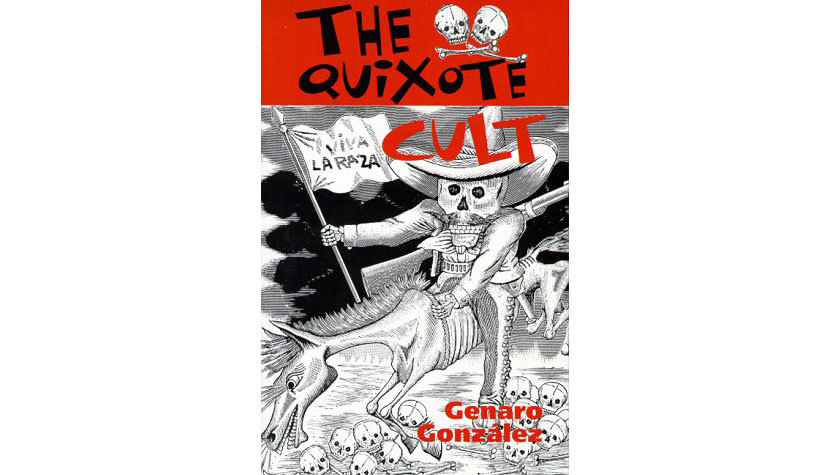

There’s a scene early in Genaro González’s little-read second novel, The Quixote Cult, where the protagonist and narrator, De la O, is invited by his friend Pablo, who works part-time at a supermarket, to help out at the store after most of its stockers are picked up and deported by the Border Patrol. It’s the late Sixties, near the border in South Texas, and De la O, a teenager from the barrio, gets stoned for the first time behind some trash bins with Pablo and Lucio, the privileged, well-read son of the store’s owner. De la O discovers Surrealist ideas through Lucio, and the magazine delivery van that miraculously carries Henry Miller books, along with paperbacks from Olympia Press—titles nearly impossible to find in South Texas at the time. This type of access is something like contraband for De La O and his friends, who are just foaming at the mouth to be part of the counterculture happening in the rest of the country—seemingly absent from the border reality surrounding them.

I was twenty in the year 2002—four years after The Quixote Cult was published—and although I didn’t have words like “representation” then, I suppose that’s what I was craving when I found this book. My family was first-generation, moved to Alton, Texas, when I was five years old. Unlike my Mexican American friends, who hardly knew Spanish, or if they did were often something like ashamed to speak it, I was raised in a strictly Spanish-speaking household. We didn’t have cable television, and the two Mexican television channels were always clearer than the American networks from our trailer’s rooftop antennae.

“Economically, the best I can hope for is to end up unlike my ancestors,” de la O thinks, when he gets to college. I was in my freshman year of college, the same year I’d drop out, when I found this book at a gift shop in a little museum in Edinburg, Texas. Something about the Posada cover design—the title, which suggested darkness, punk rock, and revolution. I opened it, and read the first page, which had references to outer space aliens on acid and people getting stoned.

Only a few novels at that time had been published and widely circulated by anyone from the American side of the Texas/Mexico border. I jumped to read them when I heard one existed. They tended to be realist, often starkly so, very much derived from the mid-twentieth-century American tradition. After reading that first page I knew immediately The Quixote Cult was unlike any of those other novels—that it was something unique and special, in a league of its own.

Vietnam, Dr. King’s murder, the Chicano movement happen through the eyes of this border kid with big dreams, while he’s learning about weird literature by authors like Alfred Jarry, and having stoner philosopher friends who flirt with the occult, petty crime, and anarchism. People talked like I knew them to talk in South Texas, characters expounded about deep things or nothing at all in a mixture of slang, English, and Spanish, as De la O took it all in. Though neither I nor any of the mostly Mexican American people I grew up with ever used words like la raza or Chicano, I related to this book immediately. It would haunt me through the rest of my twenties. I slowly discovered that if I ever attempted to write an autobiographical novel in the first person it would just be a ripoff of what González accomplished here, and after many failed attempts I left the idea of sticking to realism in my own work altogether.

Reading The Quixote Cult again, nearly twenty years later, the flaws in the book are more palpable, aside from the editorial decision from the publisher to keep Spanish punctuation out of the text. I’m not sure the present tense was the best way to tell this story, but I roll with it and it works most of the time. De la O’s young male gaze feels dated, though it’s hard to think of a parallel with another Mexican American border writer of his time who attempted to write something that feels at least honest, if flawed, around sexuality. González wears his influences on his sleeve, taking bits from Beat writers, Hemingway, Hunter S. Thompson, and making them completely his own. The Quixote Cult is definitely an artifact from the twentieth century. One that depicts a time and place like no other, that deserves to be wider read.

Fernando A. Flores was born in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and grew up in South Texas. His debut short story collection Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas was published in 2018, and in the following year his novel Tears of the Trufflepig was hailed as “a stupendous ride” by Sandra Cisneros and as “a strange, dreamlike landscape of mystical encounters and psychedelic visions” by Sam Sacks in the Wall Street Journal. His fiction has appeared in Frieze, the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, and Ploughshares, among other outlets. Flores lives in Austin, Texas.