From Lafcadio Hearn: American Writings

When he died in 1904 at the age of fifty-four, Lafcadio Hearn was one of the world’s most famous writers, the author of twenty-nine books, ranging from folklore collections and cookbooks to novels, translations, and travel essays—“none of which can compete, in terms of sheer Dickensian horror and pluck, with the story of his own life,” wrote Jonathan Dee in The New Yorker.

He was born Patrick Lafcadio Tessima Carlos Hearn to a Greek mother and an Irish father on the Ionian island of Lefkada, abandoned by his parents to the care of a great-aunt in Dublin, packed off by a guardian to a Catholic boarding school in France at the age of twelve, and then educated at a preparatory school in England, where a playground mishap resulted in the complete loss of vision in his left eye. In 1869, at the age of nineteen, his guardian sent him penniless to the United States, where he eventually became a journalist in Cincinnati and, later, New Orleans. He remained in the United States, with a two-year stint in the West Indies, until 1890, when he emigrated to Japan. During the last fourteen years of his life, he gained fame in the West as an interpreter of Japanese culture, and the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum, founded in 1933, remains one of the Chūgoku region’s most popular tourist attractions to this day.

The two decades Hearn spent in America were the formative years of his writing career. Soon after the nineteen-year-old immigrant arrived in Ohio in 1869, he found work at the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, where he wrote articles on a wide range of subjects, from Henry James to the occult. When the newspaper’s management found out about his “secret” marriage to Alethea Foley, a Black woman who had been enslaved as a child on a farm in Kentucky, they fired him “for deplorable moral habits.” He went to work for the Cincinnati Commercial, where he published his articles either anonymously or under a pseudonym. In 1877 he and Alethea separated, and he moved to New Orleans.

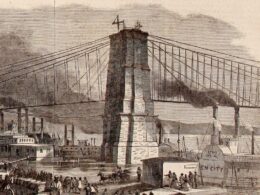

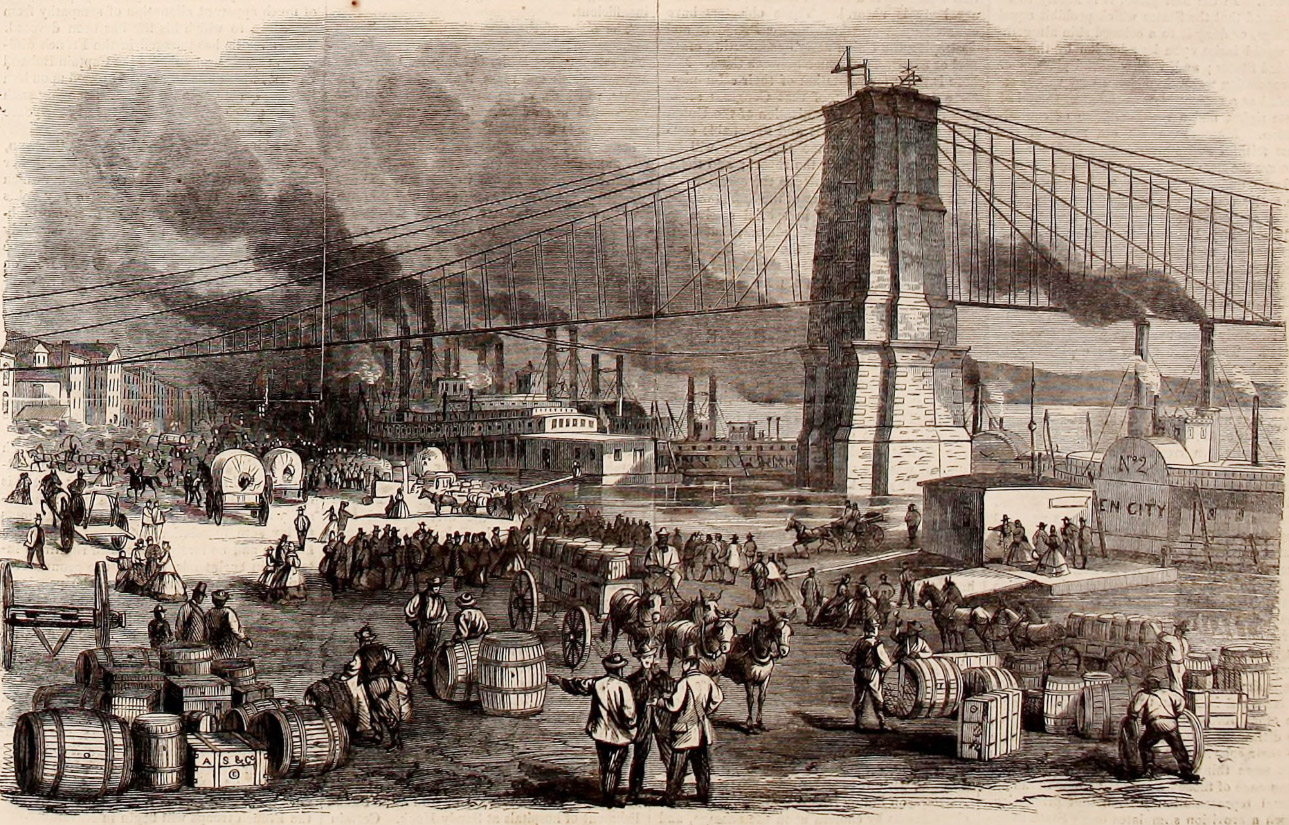

One of his better-known articles from his days at the Commercial is “Dolly,” a profile of a young, carefree woman who lived among the “roustabouts” who populated the Black neighborhood alongside the Ohio River levee. It was a part of town that few white residents entered but that Hearn comfortably frequented—visits that resulted in a series of articles about “levee life.” You can read “Dolly” at our Story of the Week site, which includes an introduction offering more detail about Hearn’s years in Cincinnati.